Carroll Yesteryears

10 August 2008

Patent Medicines Once Abounded

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Anyone watching TV this summer has probably chuckled over the country and western group extolling the virtues of Viagra with its song, “Viva Viagra.” Reading patent medicine advertisements from long ago provides similar amusement, or at least produces a grin. If Lydia Pinkham’s pills were advertised today, there would surely be a catchy jingle; the pills would be an interesting color; and a pretty girl or handsome fellow would swallow them with a smile.

Patent medicines were not usually patented, they were simply trademarked, and distribution of them began early. Some of America’s first settlers arrived with English patent medicines tucked in the corner of a trunk, but they could also buy them from postmasters, grocers, tailors, or a variety of other merchants. By the 1800s, these compounds were “sold with colorful names and even more colorful claims.”

Most patent medicine producers used similar ingredients – vegetable extracts suspended in generous amounts of alcohol. Some medicines were quite harmless, consisting of nothing more than powdered chalk, while others might have opium, morphine or cocaine added. And there weren’t restrictions on the quantity you could order or ingest!

A store that opened in Westminster in 1835 sold medicines and drugs with names such as “itch ointment,” “ipecacuanda,” “snake root” and “worm-destroying syrup.” Heavens only knows what today’s Food and Drug Administration would have thought of worm-destroying syrup! Laudanum, a tincture of opium, could be purchased over the counter. I don’t believe paregoric, also an opiate, required a prescription when I was growing up, and I distinctly recall how good it tasted when my mother rubbed it on my gums while I was cutting teeth.

Many doctors disapproved of these concoctions, but their widespread sale and constant advertisement in newspapers attest to their popularity, even if the cures never matched the claims. Almanacs were frequently printed by patent medicine companies, ensuring that the products caught your eye as you consulted the almanac.

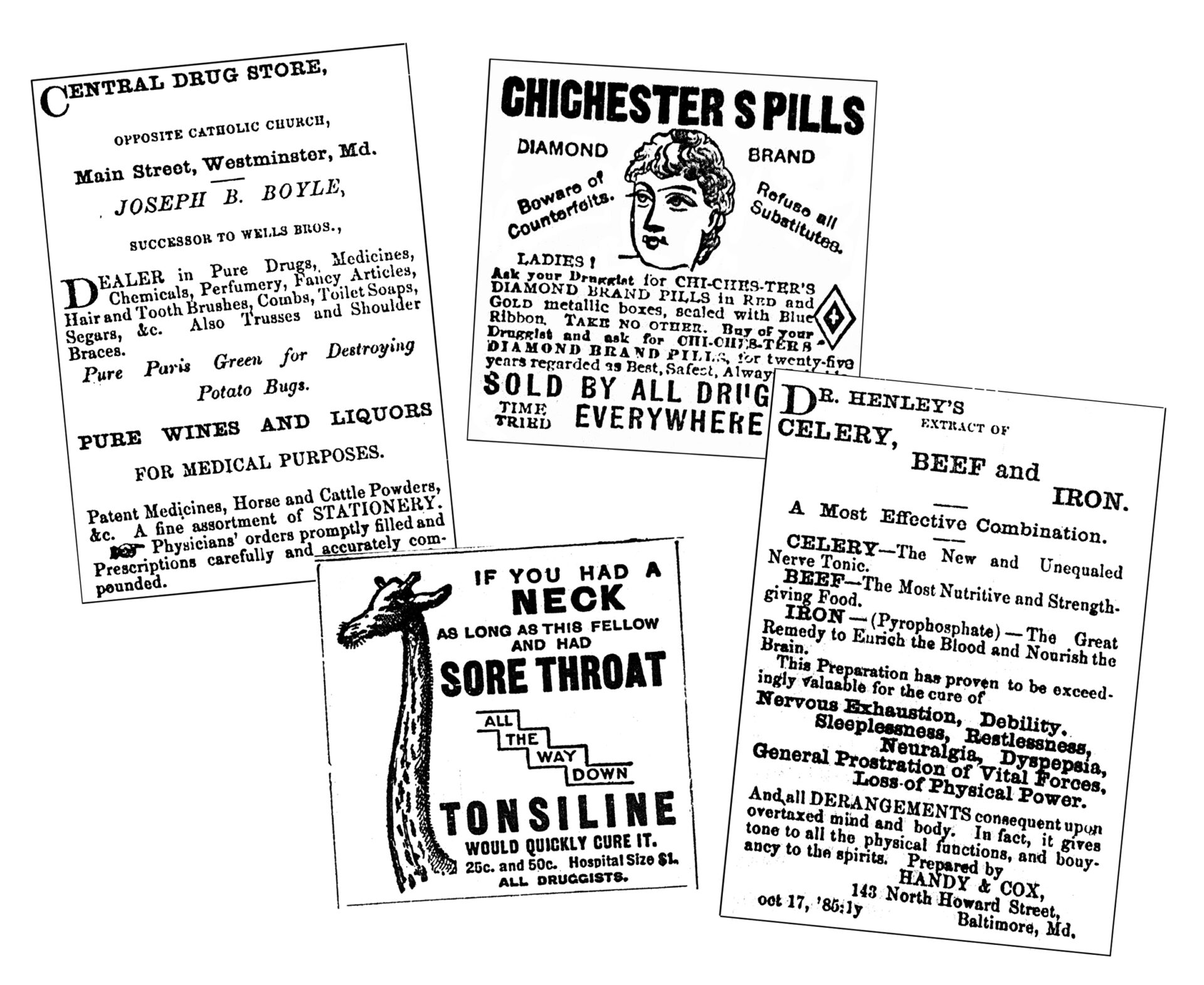

Lots of patent medicines targeted women suffering from “female complaints” or people who claimed a general malaise. An advertisement for Dr. Henley’s Extract of Celery, Beef and Iron said the product “has proven to be exceedingly valuable for the cure of nervous exhaustion, debility, sleeplessness, neuralgia, dyspepsia, general prostration of vital forces, etc.” I thought this compound sounded as if it might offer real value but, on further consideration, curing sleeplessness and nervous exhaustion made me suspicious alcohol could have been its most effective ingredient.

Another medicine called “Volina Cordial” promised to cure indigestion, weakness, chills and fevers, malaria, liver complaint, kidney troubles, neuralgia and rheumatism. “It is invigorating and delightful to take, and of great value as a Medicine for Weak and Ailing Women and Children. It gives New Life to the whole System…” An accompanying booklet called “Volina” told the user how to treat diseases at home.

Tutt’s Liver Pills were “an absolute cure for sick headache, dyspepsia, sour stomach, malaria, constipation, torpid liver, piles, jaundice, bilious fever…” “Chichester’s Diamond Brand Pills” for women were sold in red and gold metallic boxes sealed with blue ribbon. One questions whether the buyers needed the pills or just wanted the boxes! Dr. Halliday had a sure cure for corns which “stops all pain – takes “M” out by the Roots.” This locally-manufactured drug cost just twenty-five cents.

In the 1880s, Joseph Boyle’s Central Drug Store in Westminster sold drugs, medicine, chemicals, perfumery, soaps, trusses, hair brushes, Paris Green for destroying potato bugs…and “pure wines and liquors for medical purposes.” Without sulfa drugs, penicillin, various “mycins” and other modern cures, our forefathers turned to what their doctors prescribed… or something in a fancy bottle with an eye-catching label.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo caption: Typical advertisements for nineteenth century patent medicines made broad claims about their effectiveness and used a variety of approaches, including humor, to attract customers.