Carroll Yesteryears

11 April 2021

By Any Name, Many Riding the Rails Wound up in Carroll County

By Austin Hewitt

America’s poor who wandered the country have been called many things: tramp, hobo, bum, loafer, knight of the road. An anonymous Depression Era saying put it this way: a tramp wanders and dreams, a hobo wanders and works, and a bum neither wanders nor works. Have you wondered when and why the poor started traveling the country? They were part of American life dating to colonial days when their numbers were relatively small. Unexpectedly, in the 1870s, a mass population movement began. Tens of thousands of men were on the roads and rails searching for work. By 1877 it was estimated that there were 100,000 tramps, a number that had a large impact on towns near railways.

The story of tramps in Carroll County and the nation is not well researched or documented. The first record of tramps in Carroll County appears in the September 1870 report of the almshouse caretaker. He noted that 742 tramps were provided support between March 1, 1869, and March 1, 1870. Although the almshouse was built in 1852 to care for local poor, that is the first mention of tramps. They appeared in most reports through 1891 and were last referenced in 1905.

Why did tramps begin to travel in the 1870s? The country was recovering from the Civil War. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers returned home from the war. One theory is that many tramps were soldiers who could not adjust, were dealing with the Civil War equivalent of post-traumatic stress, and began to wander the country. The Western Maryland Railway reached Westminster in 1861 and New Windsor and Union Bridge in 1862, but the transcontinental railroad, completed by 1869, allowed men to ride the rails clear across the country—legally or illegally.

The transition of the country from agrarian to industrial also contributed to a wandering population. The Financial Panic of 1873 was felt throughout the 1870s and sent thousands of workers on the road in search of jobs. How many passed through Westminster? Tramps are specifically referenced in almshouse records in seven years between 1877 and 1891. Over 13,000 tramps visited the almshouse in those seven years. In 1875, the population of Westminster was about 3,200. In 1877, the almshouse fed 2,468 tramps two meals a day and offered them a bed as well. That is an amazing number for a town the size of Westminster. It also explains why city and county leaders sent as many as possible to the almshouse, hoping to minimize the impact of tramps on town businesses and local farms. When the number of tramps became too great for the almshouse, they were housed in the county jail. Despite helping this many tramps, Westminster’s Democratic Advocate reported numerous instances of thefts, assaults, and public drunkenness they committed during the 1870s and 1880s. There were also letters and editorials expressing the communities’ displeasure with tramps.

Serving this population was a major, unanticipated use of the almshouse. Maryland required every county to operate an almshouse to care for the local poor. Carroll decided to operate a farm, assuming most poor were farmers and could work the farm to reduce costs. It was decided that tramps would be provided supper, a bed for the night in the men’s dormitory, breakfast, and then were expected to move on. They were allowed to stay longer in the winter if the weather was bad. The 2,468 tramps in 1877 ate nearly 5,000 meals which significantly increased the cost of operating the facility.

How many tramps stayed at the almshouse after 1905, the last year their number was reported? It is believed that World War I veterans also had trouble adjusting to life back home and then were impacted by the Depression. A Letter to the Editor in the Nov. 4, 1932, Carroll County Times from a WWI veteran said society labeled them “intemperate grafters,” but he would say they were “a hero in war, but a tramp in peace is a veteran.”

One would expect the number of tramps travelling through Westminster to be large during the Great Depression which began in 1929. It was estimated that more than one million poor were traveling the country in 1937, but Carroll County newspapers make few references to them. In 1934, The Carroll Record made two mentions of hoboes in Taneytown. “With warmer weather has come a reduced demand, from hoboes, for a ‘few old papers, boss.’ We used to think these gentlemen of the road were strongly inclined to be seekers after up-to-date news; but it appears that they make beds of the papers, and thereby add to their comfort.” Another small item in the local news said, “The hobo crop has apparently increased—harbingers of Spring, like robins and bumblebees, only different.”

One hint of how many transients may have visited the Almshouse during the Great Depression appeared in an article in the Carroll County Times on July 2, 1937. Hampstead native The Rev. Robert H. Hoover was known to be a friend of tramps. As pastor of a church in Perryville in Cecil County, he estimated that he averaged helping three tramps per day from 1928–1937. If one church could serve more than 1,000 tramps per year for a decade, the almshouse likely served many more between 1869 and 1941. One could easily imagine visits from 100,000–150,000 tramps—an impressive service to the community that was not envisioned when it was built.

If you are interested in learning more about the almshouse, the Historical Society of Carroll County is hosting a Zoom Box Lunch Talk by Bev Humbert on April 20, 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm. Registration must be completed at least 24 hours in advance on the Society’s webpage, www.hsccmd.org.

Austin Hewitt is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County. He is also a docent at the HSCC and has experience as a docent at Gathland State Park, Washington Monument State Park and the Carroll County Farm Museum.

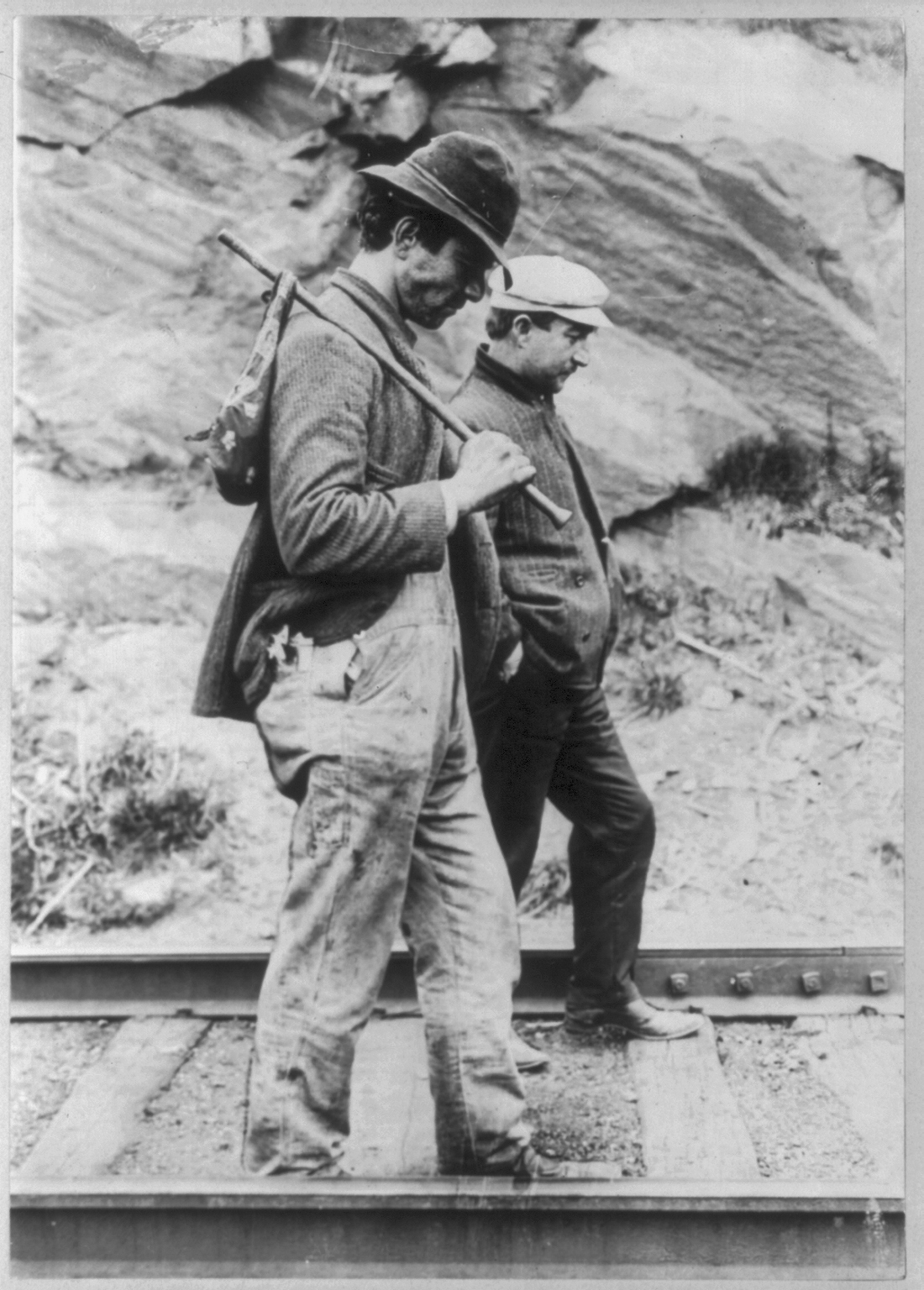

Two hoboes walking along railroad tracks, after being put off a train. Tramps and hobos had a major unexpected impact on communities nationwide that were on a railroad.

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Men’s Dormitory of the Carroll County almshouse. Tramps were housed for one night alongside permanent residents of the almshouse.

Photo Courtesy of the Almshouse Library.

Drawing of the Carroll County almshouse farm. The Men’s Dormitory was adjacent to the main house. A covered walkway was added in the 1920s. Today it is the Living History Center of the Carroll County Farm Museum.

Drawing Courtesy of the Almshouse Library.