Carroll Yesteryears

13 October 2019

Conestoga Wagon and Appropriate Image for the Carroll County Seal

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

What story lies behind the Conestoga wagon at the center of Carroll County’s official seal? I was definitely in the dark for years and now am ashamed that my lack of county history was to blame. A friend recently referred to these wagons as the tractor trailers of their day, and that is an excellent analogy. They were what transported huge amounts of freight throughout our region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and figured prominently in its economic development. The Conestoga wagon is a good image for our seal. Research shows that the period between 1790 and 1840 was the “golden age” of farming in much of central Maryland and Pennsylvania. Although tobacco was still an important crop on the Eastern Shore and in southern Maryland, farmers in south-central Pennsylvania and northern

Maryland were sending their products, often as ground grains, to Baltimore for export around the globe. Hilly terrain meant they couldn’t do what tobacco farmers did—roll huge barrels across flat landscapes until they reached a port.

It took a combination of legislation and technical ingenuity by Marylanders and Pennsylvanians to conquer the challenges of moving heavy freight over the hills and valleys of the Piedmont region. Legislation came from the state and federal governments urging construction of turnpikes to replace the poorly built roads throughout the region. Technical ingenuity was supplied by Pennsylvania Germans from Lancaster County who designed Conestoga wagons.

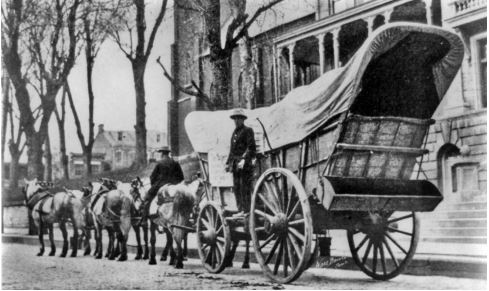

These innovative vehicles were built with the floor curved upward at each end to keep the contents from tipping and shifting along the route. An average wagon was long (18 feet including the tongue), narrow (four feet), high (11 feet), and could carry up to six tons of cargo. The seams of the body were caulked with tar to prevent leaks while crossing streams. For protection of the cargo against bad weather, they had a sturdy white canvas cover. On a rod attached to the harnesses of the lead horses often hung a series of small bells that jingled as the wagons moved along.

Forests in the mid-Atlantic region yielded excellent timber for constructing a very sturdy frame and suspension.

Although the wheels were made of wood, they usually had iron rims. Each wagon carried a toolbox for repairs plus water and feed for the horses. Teamsters often walked beside their wagons so they could access the brake handle on the left side between the two wheels. There was a pull-out board (lazy board) in case they wanted to ride on the long journeys but still reach the brakes quickly if necessary. Records show these huge vehicles had significantly better braking and steering mechanisms than average farm wagons of the day. Pulling tons of goods over hilly terrain required medium to heavy draft horses. Farmers from the Conestoga Valley of Pennsylvania and elsewhere gradually bred a strain of animals for that purpose. Most illustrations show the wagons were pulled by teams of four to six.

I ran across a short article in a 1919 issue of the Automobile Club of Maryland Motorist which included a history of the word “stogie.” It originated with the cheap (four for a penny) cigars made in Washington, PA, and smoked by the rough and ready teamsters who plied their routes in Conestoga wagons. The trips surely must have been long and tedious, but you needed to keep your eyes on the road, so you couldn’t whittle, read, or drift off to sleep. You could, however, smoke cigars and talk to the horses. Maybe you could even do a bit of singing or whistling! The turnpikes built across both Maryland and Pennsylvania between the 1790s and 1820s were a vast improvement over earlier roads. Crushed stone or even macadam became the roads’ base. Steep gradients were reduced to manageable inclines.

Better bridges made stream and river crossings easier. The turnpike that passed through Reisterstown, Westminster, and north into Pennsylvania was a full 24 feet in width, so it allowed the huge wagons to pass each other easily. In many instances, experienced civil engineers oversaw construction of these new roads. Taverns developed along the turnpikes to serve the needs of teamsters and their animals. They were located not only in towns, but everywhere on the routes, especially where steeper inclines in and out of river valleys challenged both man and beast. It must have been quite impressive to see long lines of these behemoths winding slowly across the region as they headed toward the port of Baltimore. In August 1925 a reporter from the Baltimore Sun interviewed nonagenarian William L. Ritter as he sat on the porch of his Reisterstown home overlooking the old Baltimore-Reisterstown Turnpike. Ritter recalled “how seventy-nine years ago he and his father rumbled along the same road in a lumbering Conestoga wagon, bringing twenty barrels of flour to Baltimore.” He continued, “Those old Conestoga wagons with their heavy wheels made only about twenty miles a day despite the fact that they usually were drawn by six horses. I can remember that it

took us four days to get to Baltimore from Franklin county, Pennsylvania, this side of Chambersburg.

“Great numbers of the canvas-covered wagons used to travel the pike, long lines of them, as automobiles do now. They made a crunching sound on the gravel as they passed. Many of them were filled, as I recall, with slaughtered beef being brought to Baltimore from Ohio. A great deal of lumber also was carried that way…The road then was known as the Baltimore-Pittsburgh pike. The old Conestoga wagons, of course, were supplanted by the railroads about 1853.” By 1862 the Western Maryland Railroad stretched across the center of Carroll County from east

to west. The B&O served communities on Carroll’s southern border and other railroads crossed southern Pennsylvania. Farmers no longer needed such sturdily built wagons or huge draft horses when they only hauled their goods short distances, then loaded them onto trains. Turnpikes, however, continued to operate until the Maryland’s State Highway Administration did away with the last of them in the early 20th century.

Carroll County’s official seal with its 1837 date and Conestoga wagon only hints at a lot of fascinating history that deserves to be told. Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Image credits: #1) Library of Congress; #2) Carroll County Government

#1) A six-horse team pulled this Conestoga wagon pictured at an unknown location at an unknown time period. One teamster is riding horseback while the other is standing on the “lazy board” where he can access the brake handle.

Image captions – #2) The official Carroll County, Maryland, seal includes the date of its

founding – 1837 – and a Conestoga wagon.