Carroll Yesteryears

24 March 2013

Unveil Guns, Anvils, Freedom

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Our ancestors stay alive down through the years in the letters, photographs, and possessions they leave behind. Whatever we inherit, a love letter or a pocket watch, we treasure it for its sense of family. But we can also find a sense of family buried in the records of county courthouses, historical societies, or state archives.

Research on a family living between New Windsor and Marston nearly two centuries ago took me to the courthouses in both Frederick and Carroll counties last week, and the following story emerged from the record books there.

In February 1827, John Haines was about 57 years old. Declaring himself to be “weak and afflicted in body, but of sound and disposing mind,” he wrote a will to settle his worldly affairs. He left land and household goods to his wife Mary to ensure she would live comfortably. One item was a ten-plate stove. Among other instructions, he requested that his wearing apparel be divided among his sons, that son Michael be given his watch, and son Joel receive his gun. However when John died ten months later, the treasured gun must have gone to someone else because Joel was already dead at the tender age of nine.

Mary Haines passed away in 1845. By then, the New Windsor district where she still lived had become part of Carroll County, so I found her will and the disposal of her personal property here in the office of the registrar of wills. It wasn’t surprising the inventory named many items John had left her eighteen years earlier, even the ten-plate stove. There was no mention of a gun. At the sale of her personal property in 1846, her children bought a number of her possessions, but someone outside the family paid 4 cents for a powder horn which likely had belonged to John. Who owns the gun and powder horn now? Wouldn’t descendants enjoy knowing this background on the Haines family’s life.

Resources other than estate papers also reveal family history. Transactions of many kinds ended up in Carroll’s chattel records. Often they were bills of sale like the one in which Michael Clapsaddle of Taneytown sold Samuel Swope 350 bushels of coal, a full set of blacksmith tools – bellows, anvil, hammer, tongs – a dozen Windsor chairs, feather beds, bedding, and other household goods for $100. Obviously Swope couldn’t immediately cart away what he had purchased, so Clapsaddle gave him the hammer as a token of everything due from the sale. If you are a descendant of Michael Clapsaddle, it appears your ancestor might have been a Taneytown blacksmith in the 1840s.

The chattel records also tell darker tales. In 1842, Jacob Mearing recorded a deed of manumission for his 22-year-old slave Leah. In return for the dollar she paid him, he promised to grant her freedom on January 22, 1848, when she reached the age of 28. Tragically, there was a downside to obtaining her freedom-any children she bore over the next six years would remain slaves until they also turned 28.

What fascinating stories lie in these old records!

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer for the Historical Society of Carroll County.

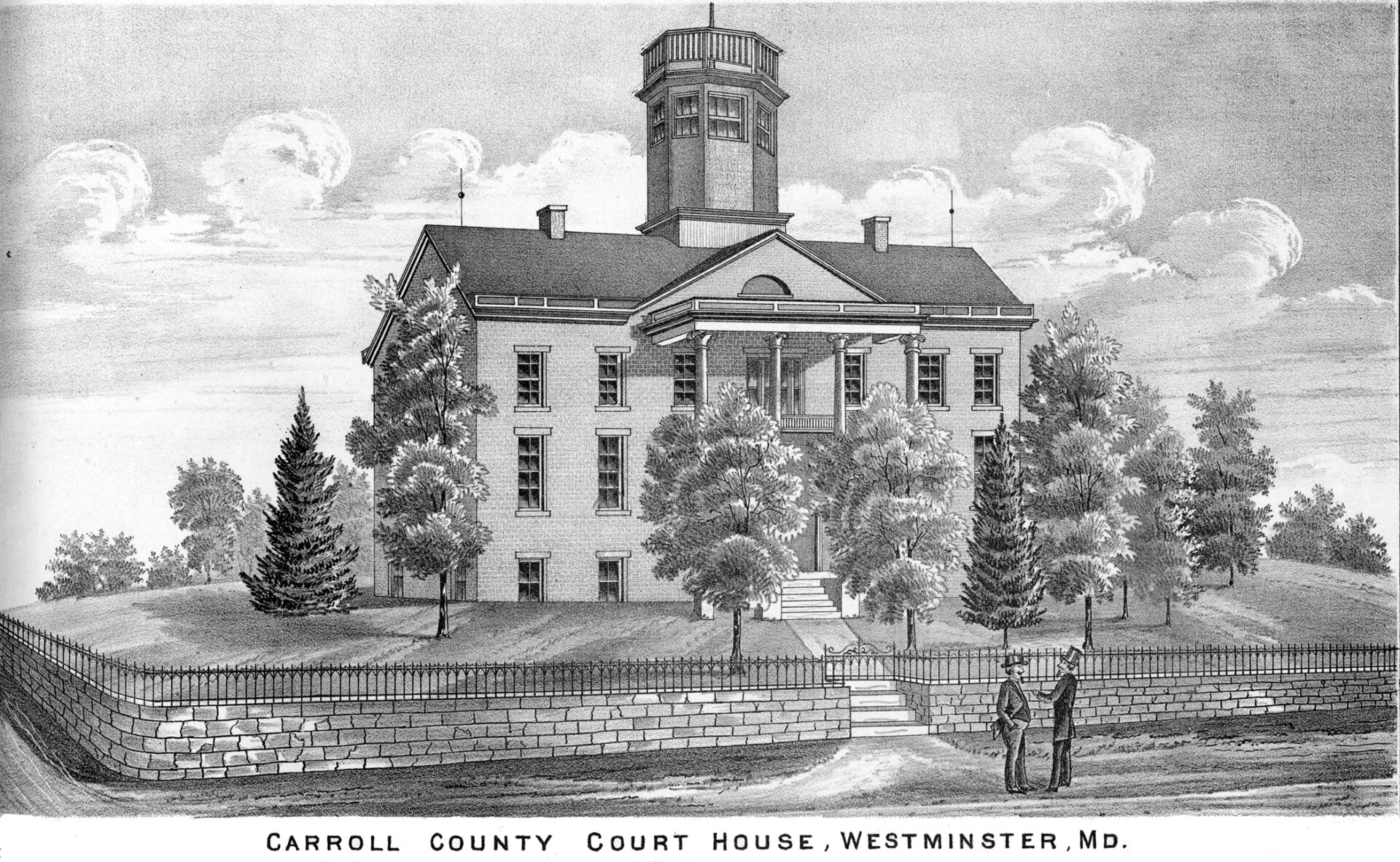

Photo credit: 1877 Illustrated Atlas of Carroll County

Photo caption: This image of the Carroll County Court House appeared in the 1877 Illustrated Atlas of Carroll County. It shows the building as it originally looked, before the wings were added in 1882.