Carroll Yesteryears

14 April 2013

Mills Sparked Economy, but Could Prove Deadly

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

So many industries have disappeared which once contributed to Carroll County’s economy – everything from cigar-making to production of wormseed oil. But thanks to local mining historian Johnny Johnsson, we know something about the quarrying and milling of flint – another of our “lost” industries.

If you’ve ever walked along the western shore of Liberty Reservoir, you probably noticed an abundance of white quartz along the trail. You may have brought home a pocketful because it is quite attractive, though you may also have cut your fingers on its sharp edges. The terms flint and quartz are used interchangeably around this area for a silicate mineral that is harder than steel. The best quality flint is pure white with no traces of iron, and for a time Maryland produced more flint than any other state in the Union.

Most of Carroll’s quarries were located along its eastern edge in the Patapsco Valley, the area now under the reservoir. They dotted the countryside from Louisville south to Marriottsville and some also occurred from Marriottsville west to Hood’s Mill. The flint was exposed at the surface – easy pickings for anyone who wanted to haul it to the two local mills. Some farmers did just that during the slack winter months when they wanted to earn extra money. The Maryland Silicate Mill operated until 1910 in Cedarhurst just north of Finksburg. Wagons loaded with flint traveled up the old Mechanicsville-Finksburg Turnpike from pits around Louisville. You can imagine what damage heavily-loaded wagons did to the turnpike surface, especially in wet weather!

A second mill, the Bennett (or Patapsco) Flint Mill, operated near Hood’s Mill along the West Branch of the Patapsco River slightly west of Sykesville. It was an old grist mill that had been converted to crush flint around 1890 at the cost of $5,000 for new equipment. Edwin Bennett, a well-known manufacturer of pottery in Baltimore, leased the mill.

Flint mills used various sources of power, including water, to crush the rock into different sizes. Gravel-size pieces were used for roofing. Somewhat smaller sizes were used for stucco. A bit was used for poultry grit, and much of it was used for abrasives like sandpaper. When ground as fine as flour, it was used in the manufacture of soap. Bennett, however, added it to pottery clay to reduce the amount of shrinkage during firing.

But flint dust could prove deadly. Some Maryland mills used a “dry” process when pulverizing the rock, and the accumulation of silica particles wreaked havoc in the workers’ lungs. Flint mills in New Jersey used a “wet” process which reduced the amount of dust and was safer for employees. Frank Brown, Maryland’s governor during the heyday of the Bennett/Patapsco mill, said, “to work in the mill even a short while means certain death, although a person may linger sometime.” The General Assembly passed a law in 1894 requiring the employees to wear respirators, but eight of them were reputed to have died during the first years of the mill’s operation, so perhaps it was best that it burned to the ground in 1895.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Image credit: Democratic Advocate

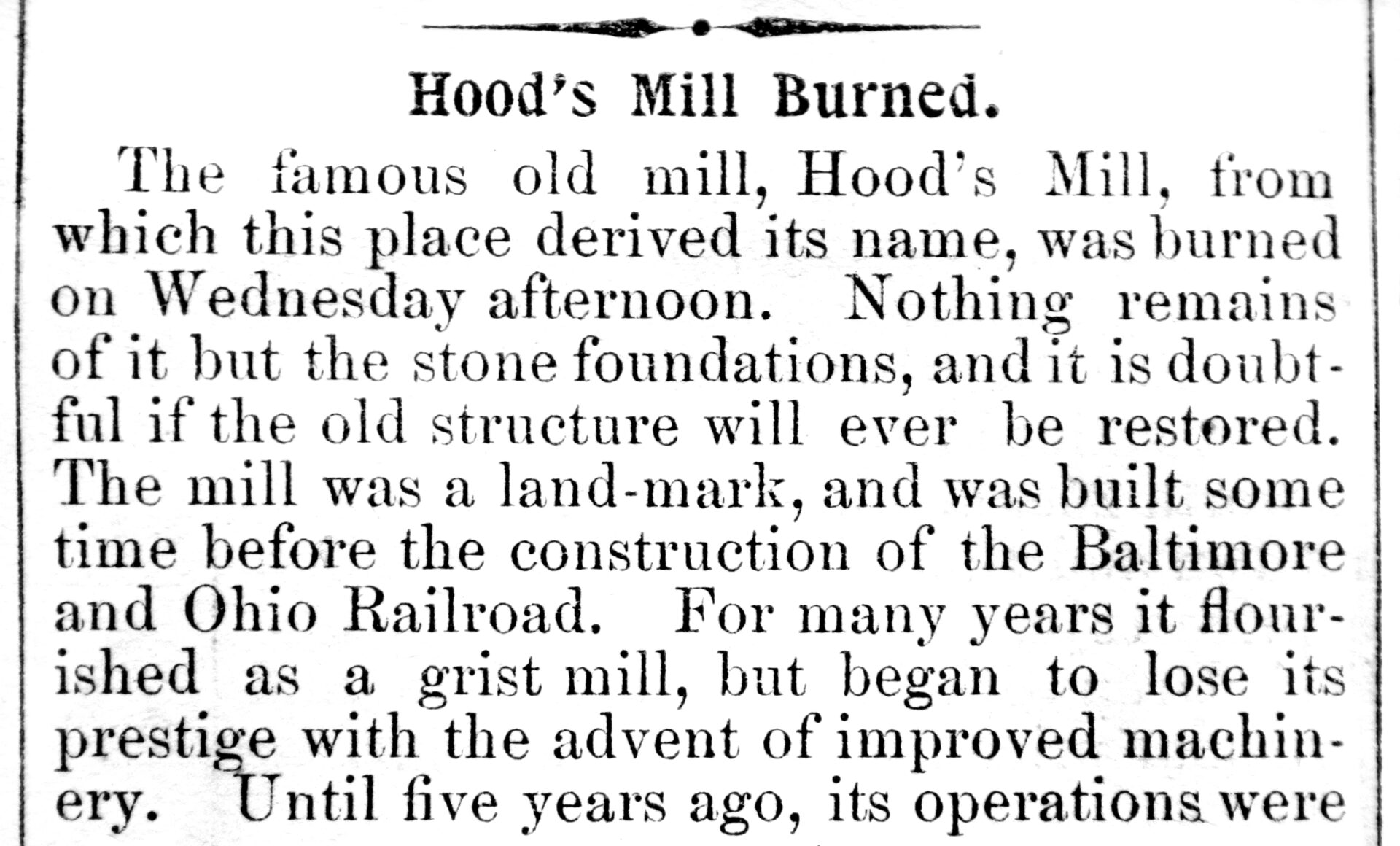

Image caption: News of the demise of the Bennett Flint Mill in Hood’s Mill appeared in the June 29, 1895, Democratic Advocate. The original grist mill, built prior to 1830, gave the community its name.