Carroll Yesteryears

29 June 2008

Mason, Dixon Made Mark in Carroll

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Couldn’t you just kick yourself sometimes! What did I have to do on October 19, 2002, that was more important than watching a re-enactment of the placing of a Mason-Dixon crownstone near Harney on the Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary? Hundreds of media types, surveyors and local residents were gathered to see a 575-pound replica of an original marker lowered into position precisely on the line where English surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon would have sunk one about 1765. Somehow I missed that special event, and I’ll probably never see the likes of it again!

Descendants of William Penn and the Maryland Calverts had been arguing over the boundary between their two colonies since Penn received his charter in the 1680s. The 40th parallel was supposed to be the dividing line, but if that had been used, Philadelphia would have ended up in Maryland! So in 1763, Charles II of England sent two of his best surveyors to settle the question. After nearly 5 years of slashing their way through primeval forests and encountering Native Americans who were not especially hospitable, Mason and Dixon finished their task of defining the boundaries between Penn’s “Three Lower Counties” (now Delaware) plus the rest of Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Every mile of the boundary was marked with a stone, but at every fifth mile the surveyors erected special “crownstones” which had been brought over as ballast in their ship. Opposite sides of the 5-foot stones were carved with the coats of arms of the Penn and Calvert families, leaving no doubt about who controlled which side. Penn’s descendants were lucky that the line was ultimately drawn about 15 miles south of Philadelphia.

The dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania was now settled, but the Mason-Dixon Line soon became important for another reason as it represented the boundary between the North and South – between free states and slave. Maryland slaves didn’t have far to travel before they reached freedom, as long as they could steer clear of slave catchers. James Pennington, a slave who escaped from his master in Washington County, MD in the 1820s, found temporary sanctuary in a home just over the border near Littlestown, PA and eventually made his way to New York City where he became a noted minister and abolitionist.

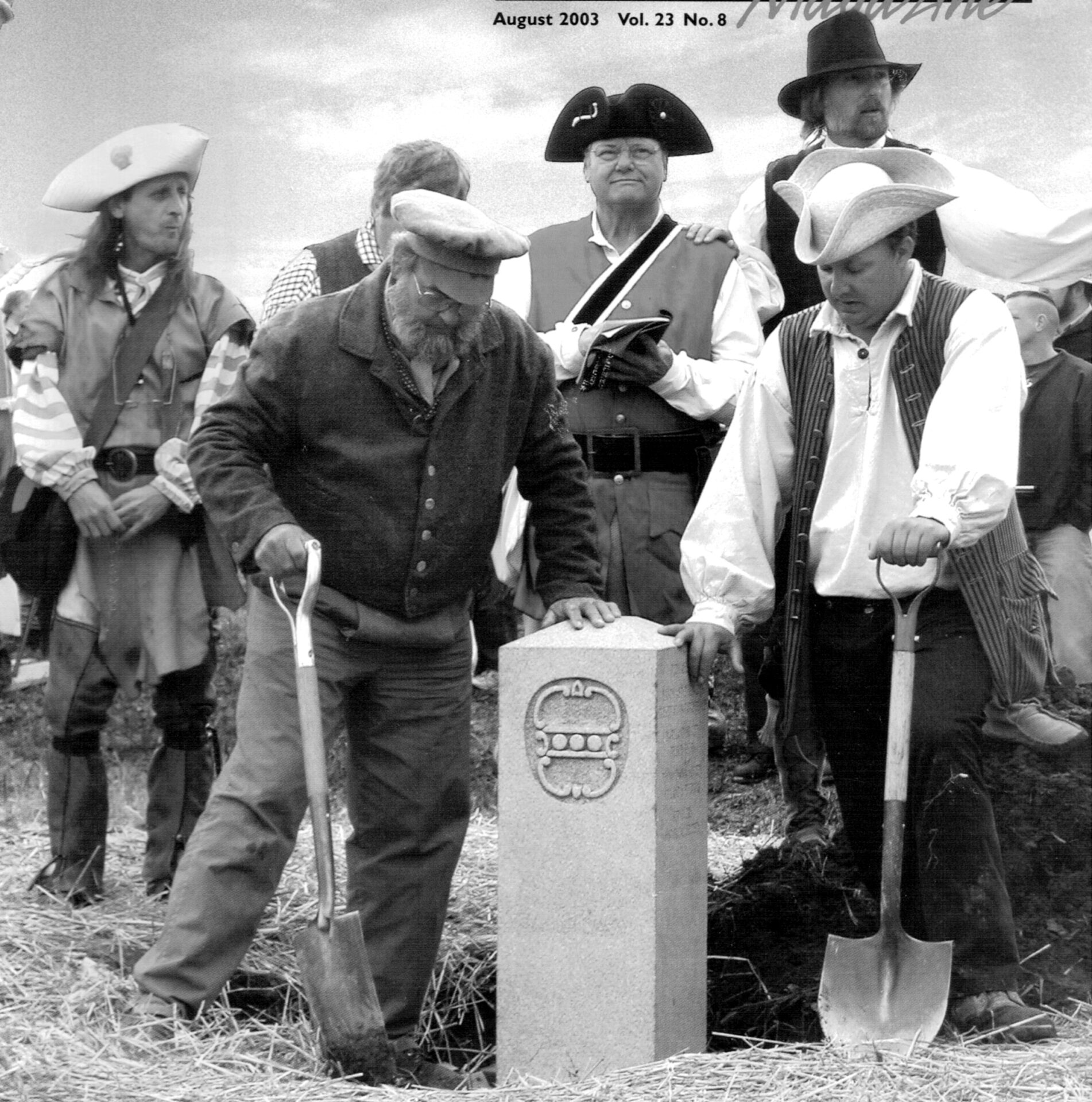

The October 19th ceremony was organized by several societies of surveyors who collected $3,000 over twelve years to replace missing Crownstone 75. Being good surveyors, they made sure the stone was correctly placed and, as they dug to pour the new base, they encountered the base of the old stone! Participants in the event were dressed in colonial garb and hauled the stone to the site on a reproduction French and Indian War wagon. They hoisted it into place using a wooden tripod and wooden block and tackle – the same equipment Mason and Dixon would have used.

Several aspects of the re-enactment were not quite authentic, but they were small concessions to the modern era. While Mason and Dixon’s crownstones were cut from very dense Portland (English) limestone, the replica was of Vermont granite and about two feet shorter. Nevertheless, it had the two coats of arms carefully engraved on opposite sides and was accurate in every other detail.

In 1983, an original crownstone, located just east of Lineboro, was moved about twenty feet from its site with the approval of all appropriate agencies because it was in danger beside a road. That event also received plenty of media coverage. We are lucky to know of two crownstones along our northern border – one original and one a replica.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer for the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Cover of Professional Surveyor Magazine, August 2003

Photo caption: Surveyors dressed in colonial garb re-enacted the placement of a Mason-Dixon crownstone near Harney in northwestern Carroll County on October 19, 2002.