Carroll Yesteryears

30 May 2021

Block Had More Than Its Share of Los in World War II

By Steve Bowersox

On Tuesday evening, August 14, 1945, the celebration marking the end of World War II began in downtown Westminster and surrounding areas.

The formal surrender of Japan would not take place until September 2, but the unofficial end had been announced earlier that day. Hundreds of cars paraded up and down Main Street with the occupants yelling out the windows and blowing horns. Large, decorated trucks carrying children and boisterous adults joined the fray. Soon the Westminster Band was included as well as two large noise-making devices on trucks owned by Thomas, Bennett, and Hunter.

Not wanting to miss out, thousands of others lined the streets to join in the celebration. According to The Times of August 17, this lasted until 1:30 a.m., and began again the next night. On Wednesday the 15th, the Westminster Band offered a concert in front of the Fire Hall on Main Street and churches opened their doors for prayer vigils. A lot of emotions were unleashed knowing that the long, costly, and deadly war was finally over and “our boys” would soon be coming home.

If you had walked farther east on Main Street that Wednesday evening, away from the concert at the Fire Hall, you might have sensed a different mood. Crossing over Longwell Avenue you would have noticed the great, gray Armory, just as you do now. In that Armory, Company H, our local National Guard unit, had trained, then gone off to war, making a name for itself with the 29th Division in Europe. You would quickly pass the U.S. Post Office, and reach the Charles Carroll Hotel, now home to offices of PNC Bank. The residents of the next block were undoubtedly grateful the war was over, but may have honored the occasion differently than the town folks near the Fire Hall.

The city block that stretches between Westminster Avenue and Lincoln Road (mere alleys today) experienced more than its share of loss during the war. The loss is really hard to comprehend when you realize it was confined to only 100 feet or so of that block. Across the street from the Charles Carroll Hotel was the City Garage.

The eastern boundary of the block was the Opera House. For those of my generation, the block was also home to the Davis Library. Between June 7, 1944, and December 5, 1944, that short strip of Main Street experienced four war deaths.

Donald Myerly lived on East Main Street, although not on that block. What ties him to the area is that he was a night attendant at the City Garage. Myerly was a 1936 graduate of Westminster High School where he worked on the stage crew for plays and, according to his senior yearbook, “was a handyman and was known as the High School news commentator, keeping everyone posted on current events around the world.” He graduated in the midst of the Great Depression, and worked a few jobs to help his family out, one of those was at the City Garage.

To earn a few more dollars he joined the National Guard in Pikesville, the 110th Field Artillery. With the war looming and seeming inevitable, the National Guard was activated into the U.S. Army and his unit was attached to the 29th Division. His family would have heard of the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944 on the radio well before the Friday, June 9 edition of The Times came out with headlines announcing it. The Times was only published once a week, on Fridays, at that time. The lead story talked of the invasion and that the 29th Division was involved. It is easy to imagine the anxiety a family would have felt knowing their son could be in harm’s way.

Before the ink was dry on that June 9 edition, Donald Myerly was a casualty. He died June 7 when the ammunition truck he was driving was struck by a German shell; 18 other young men lost their lives at the same time. Donald Myerly was 24 years old.

The telegram that notified the family of his fate, reached them at 243 East Main Street on a Sunday evening later that month. In a letter, Donald’s brother, Richard, later recounted what the aftermath was like— “Days of mourning followed. People came to the house in large numbers to pay their respects. It was a difficult time to say the least. Mom bore the brunt. It didn’t seem possible to me that a person could cry so much.” Down the street at the City Garage, co-workers were mourning as well. Donald Myerly is buried in the American Cemetery overlooking Omaha Beach, in France.

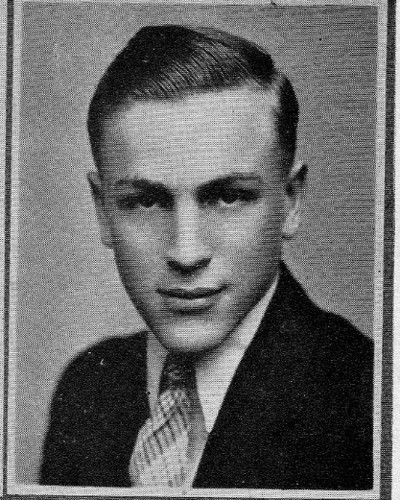

Across the street from the City Garage, at 127 East Main, sat the home of the Crandell family. Jack Crandell, WHS class of 1937, lived there. In all fairness, he had not called this his permanent address for years because he joined the Navy in 1937, and later transferred to the Army Air Corps. He and his family shared the home with his maternal grandparents, Mr. & Mrs. Edward F. Hesson. His mother, Helen, was serving as a corporal in the WACS stationed at Red River Ordinance Depot in Texarcana, TX; Jack was a 2nd lieutenant with the Army Air Force, serving in Europe; younger brother Charles, WHS Class of 1940, was in the Navy in the Pacific; sister Phyllis, WHS Class of 1942, was at Maryland General Hospital with the U.S. Cadet Nursing Corps, training to be a nurse. Jack’s father, who had served in the First World War, was deceased.

Jack Crandell received his pilot’s wings on November 8, 1943, and at that ceremony his mother, Helen, pinned his wings on him. A photo of this appeared in The Times and circulated around the country in other newspapers.

Jack was sent to England to fly missions over Europe. The June 30, 1944 edition of The Times reported that Lieut. Crandell, fighter pilot with United States Strategic Air Forces, was credited with downing two Nazi planes while on an escort mission over Europe. Not long after this, on August 26, 1944, Jack Crandell was shot down while on a mission over Luxembourg. At first he was listed as missing, but the War Department received a message from the German government through the International Red Cross that he had, in fact, been killed. Jack was 24 years old.

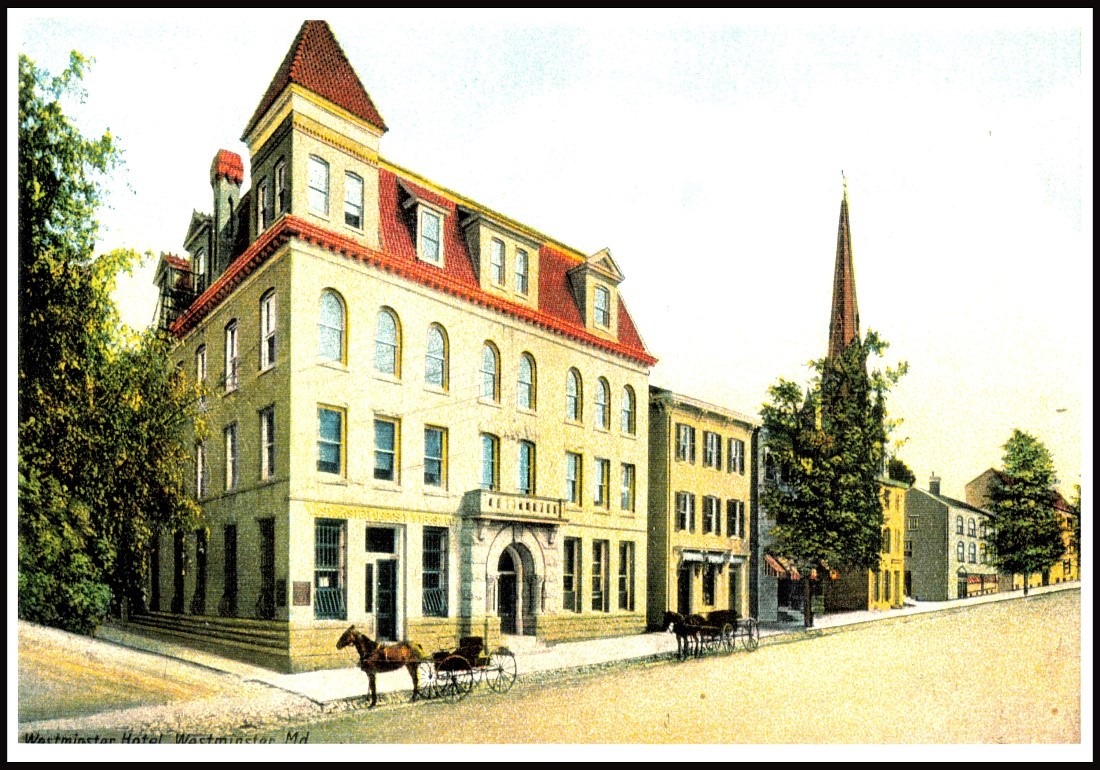

A few doors down, at 121 East Main, lived the Hooper family—Edward, Robert, their parents, and a younger brother, Tom. Edward and Robert both attended Westminster High. Edward did not graduate, but Robert did in the Class of 1942 and his senior year he was the class treasurer. Prior to entering the service on March 20, 1943, Edward worked at Westminster’s Sherwood Distillery. Robert worked at the Westminster Shoe Company before entering the service on March 20, 1944. Edward trained with a tank destroyer unit at Fort Hood, TX, and went to Europe in October 1944. Robert had already arrived in September.

Just before Christmas 1944 the Hoopers were informed that Edward had been wounded on November 25, and Robert had been missing since December 3. At this time both sons were serving in France. Within the next week, the Hoopers received official word that both of their sons had been killed in action. Edward was 21 and Robert 18.

Edward was buried in the American Cemetery in the French province of Lorraine and Robert was buried in another United States military cemetery in eastern France. Later both bodies were exhumed and sent home where they now lie side by side in Westminster Cemetery.

In a six-month period, this section of Westminster, not even a full city block long, was hit with some devastating news, culminating at Christmas with the notification that two sons from one family had made the ultimate sacrifice. There are no markers to draw people’s attention to the area and its sad history. Hundreds, if not thousands, of cars drive pass every day of the week; residents walk their dogs; runners pass by. The majority go through this area without knowing its bleak history. Although the war officially came to an end September 2, 1945, for many families, including the ones above, it had ended months before.

Steve Bowersox lives in Westminster and teaches history at Westminster High School.

Image 1: Jack Crandell. 1937 Westminster High School yearbook

Image 2: Robert Hooper. 1942 Westminster High School yearbook.

Image 3: Postcard of the street approximately 1900. Courtesy of the Babylon-Dayhoff family collection.