Carroll Yesteryears

8 January 2017

Winter Ice Ritual on Mays Farm Paid Dividends Into the Summer

By Kenneth Mays

It’s the dead of winter, a good time for the reminiscence of nonagenarian Kenneth Mays about filling the ice house on his grandfather’s central Maryland farm in the 1920s. The Mays family had a large, shallow pond on their property, “the home of thousands of frogs, tadpoles, snakes, and crayfish” in the summer, and a source of ice when winters were colder than they seem to be in the twenty-first century.

One cold, clear day when Ken was between five and eight, he remembers his father, uncle, and grandfather began cutting ice from the pond to store in their ice house and were already hard at work before the winter sun was up.

They began by using an axe to break large holes in the ice so a cross-cut saw with one handle could be inserted and the ice sawn from above. Ken recalls seeing “my father standing on a large slab of floating ice after sawing it away from the main body. It was then pushed and pulled to a point in the pond bank using a long pole with a point and hook . . .” The slabs were hauled up a makeshift ramp onto the shore where they awaited transfer to the ice house on a bobsled. “It was here that the axe [again] came into play, chopping the shiny, glistening, clear ice into manageable shapes—glistening because by now the winter sun had risen over the trees. The air felt a little warmer, but not warm enough to melt the ice.” Sometimes the waiting piles of ice refroze and pieces had to be chopped apart before the bobsled could be loaded and pulled to the ice house by Grandpa Mays’ two-horse team. Unloading the sled was another job done by hand.

On the Mays farm, the log ice house was almost totally underground—about 12-14 feet long, 10- 12 feet wide and 12 feet deep. Earth covered the low walls wherever they extended above ground and the gable roof had a large overhang. A ladder attached to the inside wall below the door allowed access to the huge block of ice as it slowly melted or was chipped away. Before adding the first ice, a thick layer of fresh straw was scattered over the earth floor, and

after the last load was delivered, more straw “was heavily strewn into every part on top of this ice cube to keep the cold in and the air out.” When Mother Nature cooperated, there might still be ice in mid-summer. The Mays ice house could be filled with one long, hard day of work on the pond and loading and unloading the bobsled as many as ten times if all went well. At the end of the day, although the men would be hungry and exhausted, the horses always came first—watering them at the pump and feeding them in the barn.

Almost 90 years later, Ken Mays remembers “making and eating homemade ice cream frozen by ice cut the previous winter brought the [annual] ice ritual to its fruition on a hot July Sunday.” Kenneth Mays, guest contributor, spent many years as a teacher and principal in Carroll and Baltimore county schools.

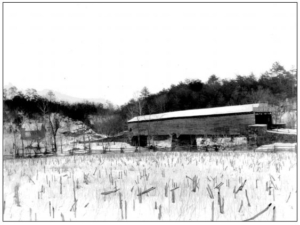

Photo credit: Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo caption: The Historical Society of Carroll County has no images of ice harvesting. This c.1900 winter photograph shows the covered bridge which once carried travelers across the Monocacy River at Bridgeport, a few miles west of Taneytown. The bridge was built in 1849 and was in use until 1932.