By Zane Wetzel

By Zane Wetzel

Its residents may not know this, but Carroll County was the birthplace and childhood home of one of the finest sculptors to come out of the United States, a man by the name of William Henry Rinehart. The fifth of eight sons to Israel aand Mary Rinehart, William was born on September 13th, 1825 in Union Bridge, Maryland, then a part of Frederick County. when Carroll County was formed in 1837, Union Bridge became part of it. During his childhood, he began exhibiting a significant talent at sculpting, something that his mother, herself a lover of poetry and the arts, chose to nurture and encourage in her son throughout his youth. By the time he reached adulthood, he moved to Baltimore to try his luck as a sculptor there, with his early works piquing the interest of some of the cities’ most influential citizens, such as merchant and art connoisseur William Walters. With the backing of Walters and several others, Rinehart eventually moved to Rome to set up his main studio where he crafted beautiful sculptures and reliefs for clientele across the world. Over the years, the Historical Society of Carroll County has made Rinehart’s life a major focus, having collected several of his pieces over the years, the following of which are shown below.

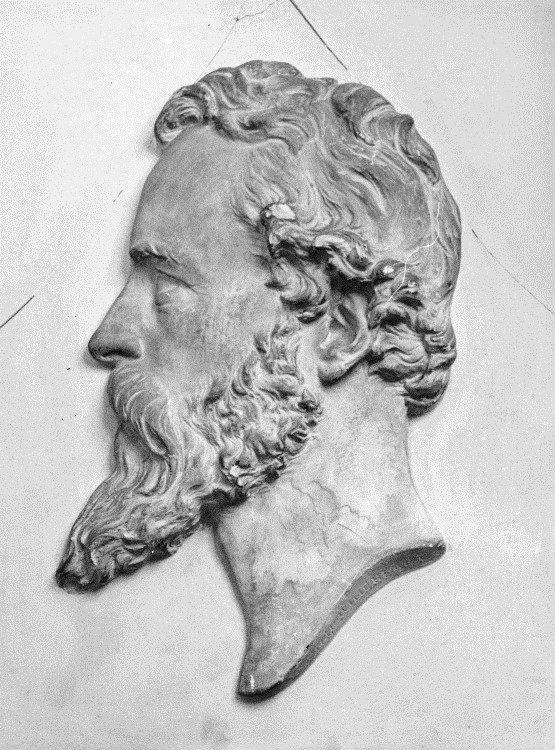

#1- Rinehart’s Bas Self-Portrait

A self-portrait bas relief of Rinehart himself, made while living in Rome around 1870.

First is this self-portrait and bas relief of Rinehart, made in Rome in approximately 1870 and donated by Evan Rinehart. A relief is a type of sculpture that projects a three-dimensional object to varying degrees from a flat, two-dimensional background. One of the oldest forms of art, relief sculptures date back thousands of years, with examples being found at the Acropolis of Athens in the Parthenon, an ancient Greek temple dedicated to the city’s chief deity and namesake, Athena. This form of sculpture was first popularized in the United States by Italian sculptors hired to decorate buildings for the Federal Government, leading their American counterparts to travel to Italy to learn more about the technique. Rinehart normally didn’t do reliefs, but he was known to have created several during his career, with this relief in particular being made in the later stages of his life.

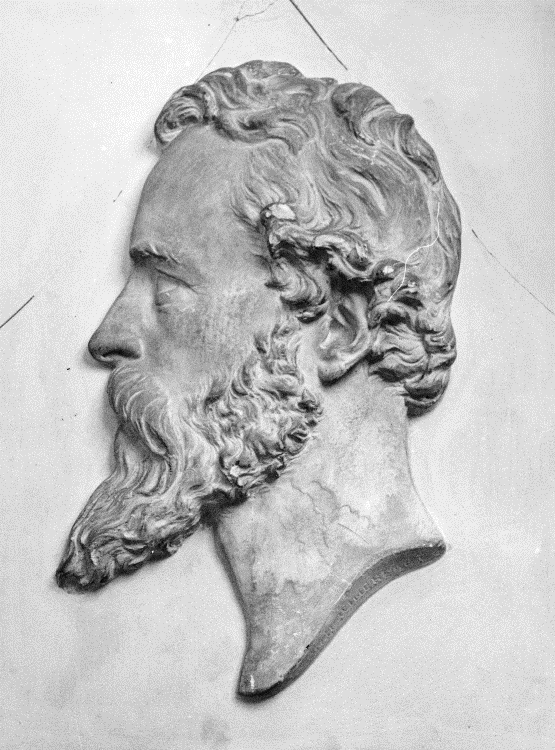

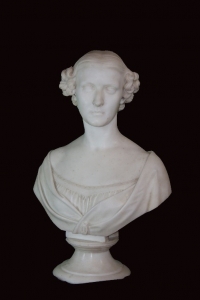

#2- Bust of Sarah Matilda Robertson Mygatt

Rinehart was better known for the busts he created for customers, carving more than a hundred between 1853 and his death.

A type of sculpting that Rinehart was better known for was creating portrait busts of clients, which brings us to our second piece, a bust of Sarah Matilida Robertson Mygatt that was made in Rome in 1860. From 1853 until his death, Rinehart carved more than a hundred busts for various customers. This was a very profitable enterprise, with most of his clients were wealthy businessmen or prominent figures who visited his studio in Rome while touring Europe. In fact, towards the end of his life, it became very popular to own a Rinehart bust. Despite the money that could be made from it, however, making portrait busts was considered lackluster for someone who wanted to do more imaginative work. Rinehart would produce his busts by molding a clay model then using that to create a plaster cast, which stonecutters would then carve the final product from marble. This particular bust was given to Ms. Mygatt, but was believed to be lost for several years. However, in 1964 the Mygatt Bust was located by Bruceville, MD, native Donald Detwilerm in the home of a New York relative. Upon its rediscovery, it was given Ms. Susan Kellog, a cousin of Sarah Mygatt, who then donated it the HSCC to add to its collection.

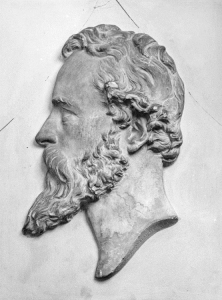

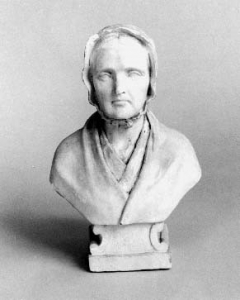

#3- My Mother

“My Mother” was one of Rinehart’s most important pieces, as it was a tribute to his deceased mother.

The final object is a plaster copy of another bust crafted by Rinehart, My Mother, made in Rome around 1868. This bust was of particular importance to Rinehart because it was meant to serve as a tribute to his deceased mother, who had encouraged him to become a sculptor in the first place. To make it look as close to his mother as possible, Rinehart sent for the cap that his mother had last worn before she died. In a poetic way of bringing his career full-circle, Rinehart combined the cap with the original clay bust that he had made as a child to create this new version. Rinehart decided to give each of his brothers a plaster replica of the original marble one that he made for himself. This copy in possession of the HSCC was believed to have belonged to his older brother, Evan Thomas Rinehart, who passed it down to his daughter, Mrs. Harry D. Williar, Jr., who then donated it to us.

Conclusion

Rinehart, like so many great people, was gone too soon. During the summer of 1874, overwhelmed by the number of commissions he was given, Rinehart chose to forgo his annual vacation to Switzerland, which led him to contract Tuberculosis, a disease that would eventually claim his life on October 28th, 1874 at the age of 49. Despite his passing at such a young age, William Rinehart remains a highly celebrated artist with his works of appearing in various art exhibits and institutions, such the Peabody and Maryland Institutes, the Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, and even the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. The works that the HSCC has are only a portion of what this son of Carroll County left behind for future generations to appreciate, monuments to the arts that fuel the heart and soul.

Extra Information

CLICK THIS LINK BELOW IF YOU WANT TO READ ABOUT OUR PAST EXHIBIT ON RINEHART:

https://hsccmd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/William-Henry-Rinehart.pdf

OR CLICK HERE IF YOU WANT TO SEE SOME OF THE WORKS FROM THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART IN NEW YORK:

Bibliography

Periodicals

Breen, Robert G. “Historical Sculpture.” The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), August 20, 1964, regional edition.

Carroll County Times. “Unlocated Bust Given to Society.” Carroll County Times (Westminster, MD), August 27, 1964.

Nonperiodicals

Doxzen, Duane. William Henry Rinehart: American Sculptor. Westminster, MD: Historical Society of Carroll County, 1995. Accessed June 26, 2017. https://hsccmd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/William-Henry-Rinehart.pdf.

Audiovisual

Rinehart, William Henry. Clytie. 1872. Marble Sculpture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/11.68.1/.

Web sites, e-sources

Tolles, Thayer. “American Relief Sculpture.” www.metmuseum.org. Last modified October 2006. Accessed June 26, 2017. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/amrs/hd_amrs.htm.