Carroll Yesteryears

10 May 2020

The Fight for Their Country: Three African Americans from Carroll County, Three Different Civil War Experiences

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

From time to time those of us writing articles for “Carroll’s Yesteryears” have recounted the stories of local African Americans who fought for the Union Army or Navy during the Civil War. The men who survived and returned to this area saw a great deal more of the country in a few short years than ever before in their lifetimes, and brought back hope for brighter futures, especially those who had been enslaved when the war began.

Joshua Dutton was 18 years old in March 1864 when he joined Co. K, 30th Regiment Infantry, United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.). This was a regiment composed of Maryland men who saw heavy fighting around Petersburg, Virginia, the last year of the war. Dutton was the slave for life of Nathan Gorsuch of Woolery District at the time he enlisted. His military record includes the paperwork detailing what Gorsuch did to receive compensation from the U.S. government for allowing Dutton to serve. First Gorsuch filed a manumission in Carroll County granting Joshua his freedom. Next he filed an “Evidence of Title” showing he had owned him since birth. Finally, Gorsuch signed a loyalty oath. Several of these documents bear the 5-cent revenue stamps issued by the United States to help pay for the war. Once the paperwork was complete and when no one questioned his loyalty, Gorsuch received $300.

Like many African American men from Carroll County, Joshua listed his occupation as “laborer.” Probably the life he led working for Nathan Gorsuch prepared him for the hard work he faced once in the army. It was well-documented that members of the United States Colored Troops usually were assigned duties involving hard labor under dangerous conditions. Dutton was discharged at the war’s end after spending many months in a hospital recovering from wounds he suffered in mid-1864. He returned to the Woolery District and appeared in the 1870 census living with his 44-year-old mother and younger brother. In 1890 he began receiving an invalid pension, and by 1910 was married and starting a family. He died in 1920 near Gamber, not far from where he was born, and probably buried in Pool’s Church Cemetery along Route 32.

Although Joshua Dutton’s life was not one of rags to riches, it seemed to have turned out quite well. His mother was alive and free when he settled back in Carroll County after the war. He never learned to read and write and remained a day laborer, but owned his home by 1900 and was surrounded by family at his death.

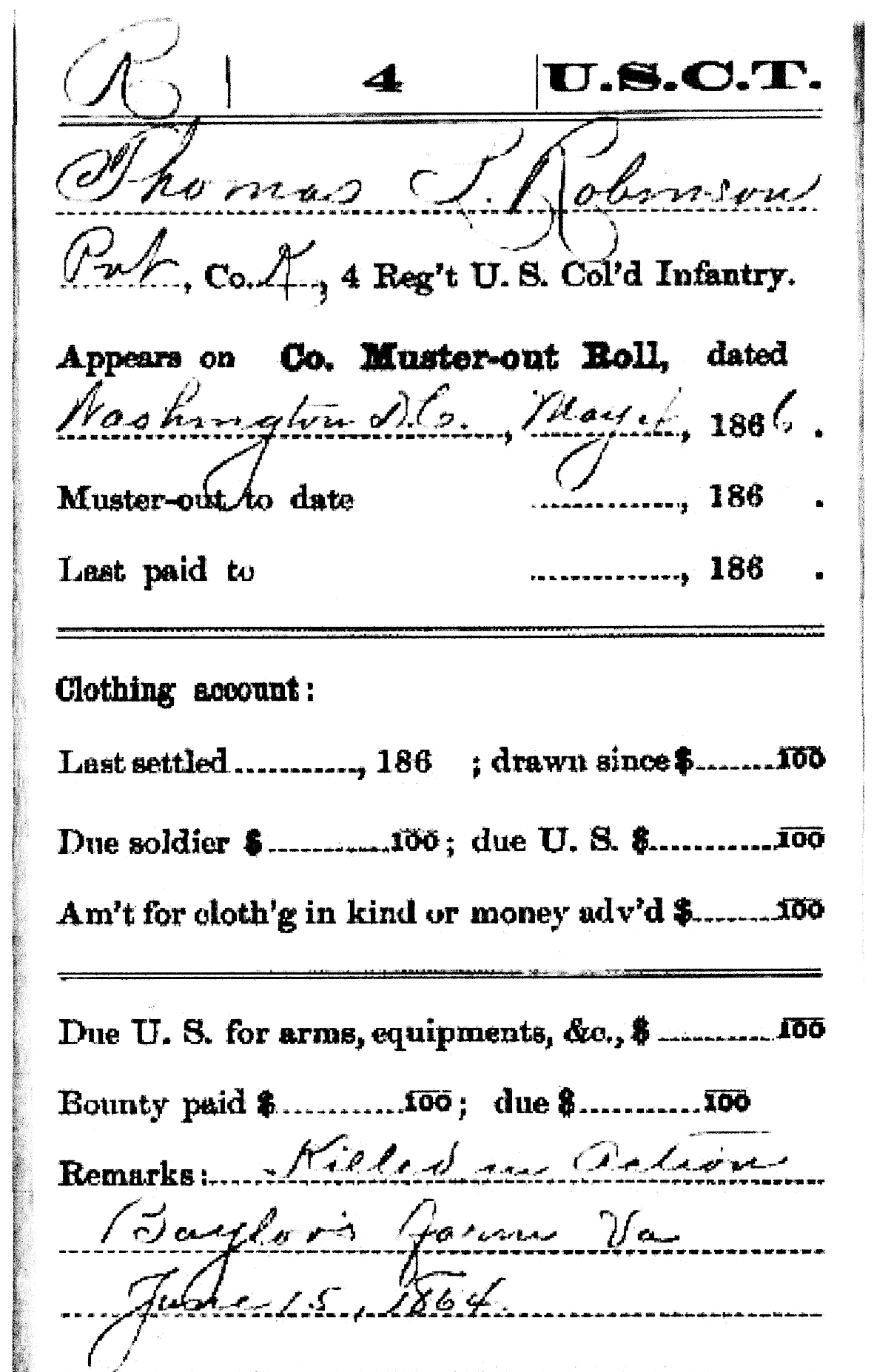

Thomas L. Robinson met a different fate when he enlisted as a free man in the 4th U.S.C.T in September 1863. He was 19 and a farmer. Black Marylanders serving in the 4th and 30th infantry regiments had similar experiences—fighting in many of the same battles around Petersburg, Virginia, and doing some of the army’s toughest jobs. Robinson was one of those who never came home. His military record shows he was killed in action June 15, 1864, at Baylor’s Farm, a skirmish near Petersburg. In looking at the records of about 50 Carroll County black soldiers, several others were killed or wounded during that relatively minor engagement that pitted untested black troops against Confederates protecting the route to Richmond. The battle proved to doubters that African American soldiers were willing and able to fight, qualities the Union Army would rely on the rest of the war.

Henry Howard’s Civil War experience was unusual for Carroll County African Americans, but it began in a familiar way. Like Dutton, he was a slave when the war started. His owner, Upton Scott, filed a manumission recorded on October 14, 1864, in Carroll County. If Scott completed the other requirements in order to collect U.S. government compensation, they aren’t easy to find. It is worth noting that roughly two weeks after Howard was manumitted, all of Maryland’s slaves were freed by the state’s new constitution. The owners of thousands of men, women, and children still in bondage on November 1, 1864, hoped the state would reimburse them for their loss of “property,” but they were never paid.

Meanwhile, Henry Howard, age 23, joined the U.S. Navy in Baltimore in April 1863 for a 3-year stint. It is unlikely he had seen a body of water larger than the Monocacy River when he boarded a vessel and sailed out of the harbor and into the Chesapeake Bay. His rank was “landsman,” not the Navy’s lowest, but almost. Hopefully he had good “sea legs” even if he had no nautical experience. Howard would find the same prejudice in the navy that black men endured in the army in spite of the fact that the navy had been integrated for many years.

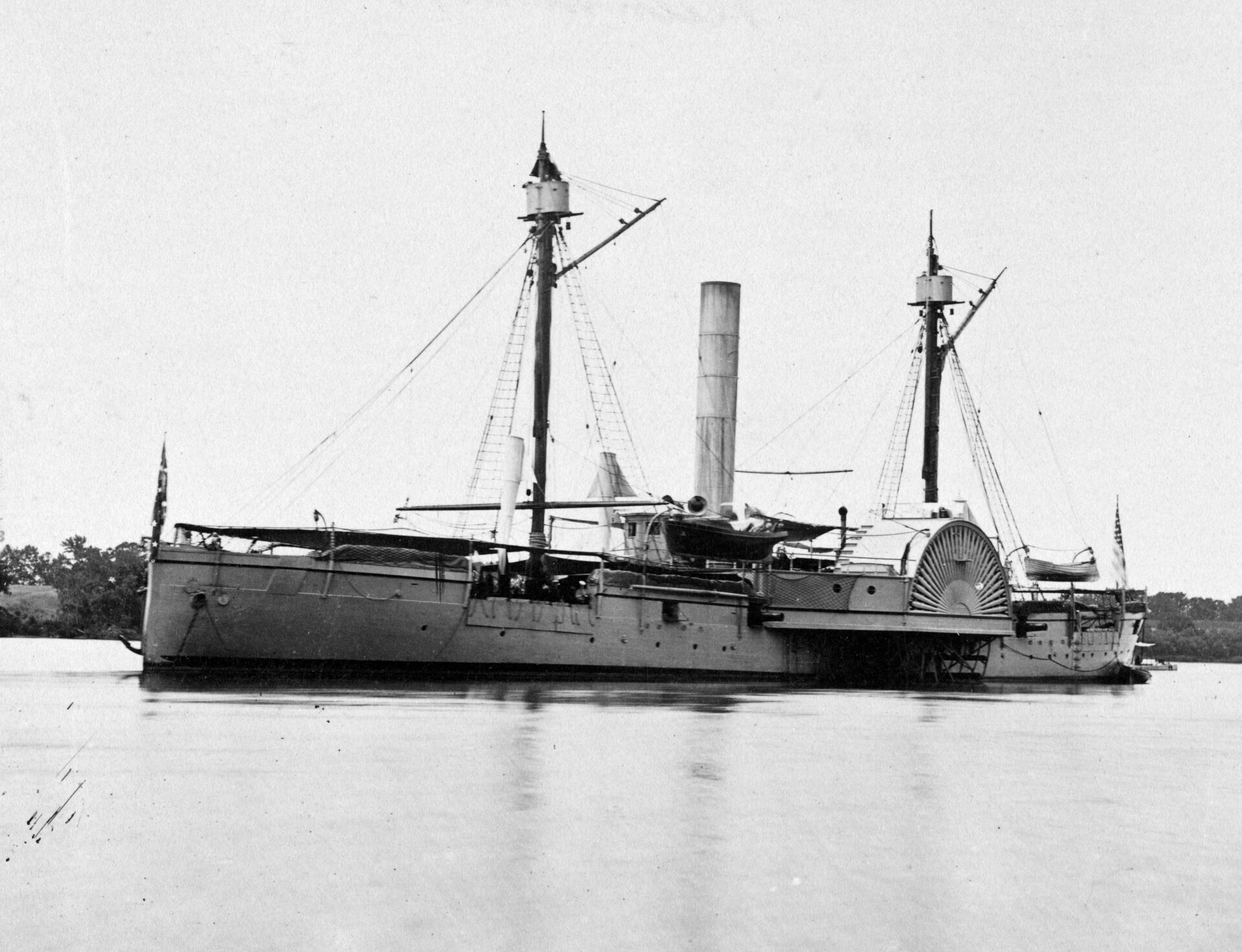

Between 1863 and 1866 Howard served on three vessels, the U.S.S. Nipsic, U.S.S. Mahaska, and U.S.S. Susquehanna. The first two were gunboats newly built in the Portsmouth Naval Yard, Kittery, Maine—part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. They operated in the waters of the Chesapeake, in the rivers of Virginia, as well as along the Atlantic seaboard in an effort to keep Confederate ports closed. The Susquehanna was a frigate that had sailed to Japan before becoming part of the blockading fleet. Officers on these vessels were white as were higher-ranking crewmen, but in battle it would seem all hands were needed. At the beginning of 1865, the Navy launched a massive attack to capture Fort Fisher which protected Wilmington, North Carolina, the last Confederate-held port on the East Coast. Henry Howard was serving on one of these vessels during that famous battle.

Howard’s period of enlistment ended in June 1866, but he re-enlisted in September for another three years. He was now 26 and a description of him included tattoos—a crucifix on one arm and the image of a woman on the other. It seemed he had embraced a sailor’s lifestyle. What he did, where he went, and how long he lived after his naval service are currently unknown, but his horizons were certainly broadened by his war-time service.

Three men… three very different experiences after leaving Carroll County to fight for their country.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Image 1 Source – Library of Congress

Image 1 Caption – This steam-powered sidewheel gunboat is similar to the U.S.S. Mahaska, one of the vessels on which Landsman Henry Howard served. The photograph was taken on the James River in Virginia.

Image 2 Source – Fold3 Military Records

Image 2 Caption – The death of Private Thomas L. Robinson, Co. K, 4th U.S. Colored Troops at Baylor’s Farm near Petersburg, Virginia, on June 15, 1864, appears on his muster-out roll.