Carroll Yesteryears

13 September 2020

Remembering Union Bridge native, Civil War soldier Isaiah Lightner

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

The great English poet Alexander Pope offered a memorable quote, “Act well your part, there all the honour lies.” How appropriate that seems to describe the life of Isaiah Lightner. His story, stretching from his birth in Union Bridge to his final days in Nebraska, reveals a man who acted well his part.

Isaiah was born October 30, 1841, to Davis and Sophia Lightner. Judging by information from the 1860 census, the Lightner family was one of the wealthier ones in the Union Bridge area and 19-year-old Isaiah lived at home while clerking in a store. Two years later, during the summer of 1862, he and many other young men from the Union Bridge and New Windsor areas joined Company F, 7th Maryland Volunteer Infantry to fight for the Union cause. There is some indication in a deed that Davis Lightner was a Quaker, and Union Bridge was a decidedly pacifist area full of Quakers and members of the Church of the Brethren, but if Isaiah acted against his family’s wishes, there is no evidence.

Many of the men in Company F must have been acquaintances, even friends, before they enlisted, and serving together would have strengthened their bonds. Lucky for them that their unit saw very little action from August 1862 until the spring of 1864. They were not in the front lines at Antietam or in the thick of the Gettysburg battle, but all of that changed when the Union Army began its Overland Campaign in early May 1864. Civil War enthusiasts recognize the names of many bloody battles in which Lightner and the 7th Maryland fought during May and June—The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna, and Cold Harbor, to name just a few. Death and/or capture occurred often. Prisoner exchanges were no longer in effect. Lightner’s friend Winfield Drach lost a leg during the early fighting; other members of Company F ended up in prison camps and died there. At one point, Isaiah and 300 others were captured for about 36 hours until freed by Union troops. For more than a month, members of the 7th Maryland endured battle after battle until the Union and Confederate armies settled in for a nine-month siege of Petersburg, Virginia.

Isaiah Lightner gradually rose in the ranks of Company F from his appointment as sergeant in 1862, through acting as 1st lieutenant during the Overland Campaign until achieving the rank of captain in December 1864. Early in 1865 he received a furlough to visit his ill mother and subsequently fell ill himself, but was back in the ranks by mid-February. The good fortune he experienced during his first 30 months of military service ended April 1, 1865, at the Battle of Five Forks near Petersburg when he was shot through both hips by a bullet that just missed his spine. He lay in a Union hospital when Lee surrendered on April 9, but for the remainder of his life he recalled the thrill of a handshake and greetings from Abraham Lincoln who visited the ward while he was there.

Back home in Union Bridge after the war, Isaiah and Jesse Anders operated a store at the corner of Main and Broadway in the heart of town. That building still stands, now occupied by “Original Pizza.” On December 3, 1867, he married Fannie (Phelana, Fanna) Haines, daughter of Stephen and Esther Haines, who lived nearby in Frederick County. Their first child was born in 1869 and in June 1870 the young couple successfully petitioned the Pipe Creek Society of Friends (Quakers) to join its congregation along with their daughter. When their second child was born later that year, his name was added to the minute book. Eventually the names of three more children appeared, although two of them were laid to rest in the Pipe Creek Cemetery between 1876 and 1878.

During the early years of their marriage Isaiah and Fannie threw themselves into working toward betterment of their Union Bridge community. They helped found the Friends Seminary of Pipe Creek, a Quaker school on Locust Street, and Isaiah gradually gained a reputation for his compassionate leadership within the Quaker community. Members of the Pipe Creek congregation felt “our friend Isaiah Lightner has received a gift in the ministry and should be recommended as a minister.” Quakers do not use the term “minister” in the formal sense used by most Protestant congregations but as a lay person gifted in offering aid and service to others. Over the next 40 years Isaiah continued to live and work following his strong Quaker beliefs.

At some point about 1876 he may have joined other Quaker missionaries working with Native Americans on the Santee Sioux reservation in northeastern Nebraska, probably leaving Fannie and his young children behind. The Society of Friends had long championed African Americans in their struggles for freedom, but now Native Americans were in need of help. In 1868 President Grant reversed the management of reservations with a new “Peace Policy” which put Catholic and Protestant missionaries in leadership roles instead of military men. The Quakers were in charge of most of Nebraska’s reservations. When President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Isaiah as the Indian Agent for the Santee Sioux in 1877, it became his responsibility to report to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, part of the U.S. Department of the Interior. It seems unlikely Isaiah was plucked directly from his role as a merchant in Union Bridge to fill the job, so he probably had been working on the reservation when he received the appointment.

Just 15 years before Isaiah arrived, the Santee Sioux had been part of a violent uprising in southwestern Minnesota and were relocated to the reservation with the goal of turning them into peaceful farmers. When Fannie and the children reached the reservation about 1878, the Santee Sioux were scarcely removed from the ways they had followed for centuries – still wearing their native dress, living in teepees, and speaking a Sioux dialect.

In an 1878 report Isaiah sent to Washington he noted, “[The Indians] have broken four hundred and sixty acres of new land during the past year, and are taking an increased interest in their farm work. This has been brought about by the hope that Congress will pass an act allowing them to take homesteads on these lands they are improving.”

The task for the missionaries was enormous, but by the mid-1880s approximately three-quarters of the Santee Sioux families were reported to be self-sufficient. Isaiah continued urging the government to grant permanent ownership of land to each family and worked with an interpreter and other missionaries to teach farming, masonry, and carpentry as well as school subjects. Compared to leading a company of 100 English-speaking men during the Civil War, the task of running an entire reservation must have been all-consuming.

The Lightners lived with the Santee Sioux until the spring of 1886. Their last two children were born on the reservation, and the older children likely attended school with their Native American counterparts. In spite of Isaiah’s good leadership, a great deal of work remained to be done by the agents who followed him. There is still much controversy over the policies followed by the missionaries and the U.S. government in dealing with the Native American populations in the 19th century.

A 350-acre farm in Platte County awaited the arrival of Isaiah, Fannie, Esther, Stephen, Lizzie, and Charles after they left the reservation. They knew the area already had a Quaker presence so Fannie and Isaiah transferred their membership from the Pipe Creek Meeting to the Genoa Meeting nearby. Still only 45 and 46, Isaiah and Fannie began working tirelessly in their new community as well as on their farm. Isaiah helped bring telephone service, continued to serve in the Society of Friends, offered farming advice, advocated for temperance and women’s suffrage, and even ran for lieutenant governor of Nebraska in 1902 on the Prohibition ticket. Although they stayed in touch with friends and family back in Union Bridge, even returning for a visit in 1899, their roots were now firmly planted in Nebraska soil. They “very successfully practiced what is known as diversified farming, having a large dairy and orchard in addition to the farm proper.”

Following Fannie’s death in 1911, Isaiah made a short visit back to Carroll County. In 1912 he married a widow with four grown children but still kept in touch with Union Bridge news, writing letters back to the newspaper when he read of the deaths of former Civil War comrades. As the years passed, he began spending the cold winter months with his wife in southern California and it was there he passed away March 2, 1923. His son Stephen brought his body back to be buried in the Oconee Friends Cemetery in Platte County beside Fannie.

There is little wonder his obituary in the Columbus [Nebraska] Daily Telegram reported, “It is impossible to sum up in a few words all the lovable traits of this kind, sympathetic man, who has so fittingly spoken the last words of comfort over the bier of so many of our departed loved ones; who was ever ready to lend a hand and be a true neighbor.” From everything that has come to light in researching Isaiah Lightner’s life, it appears he did indeed “act well his part.”

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

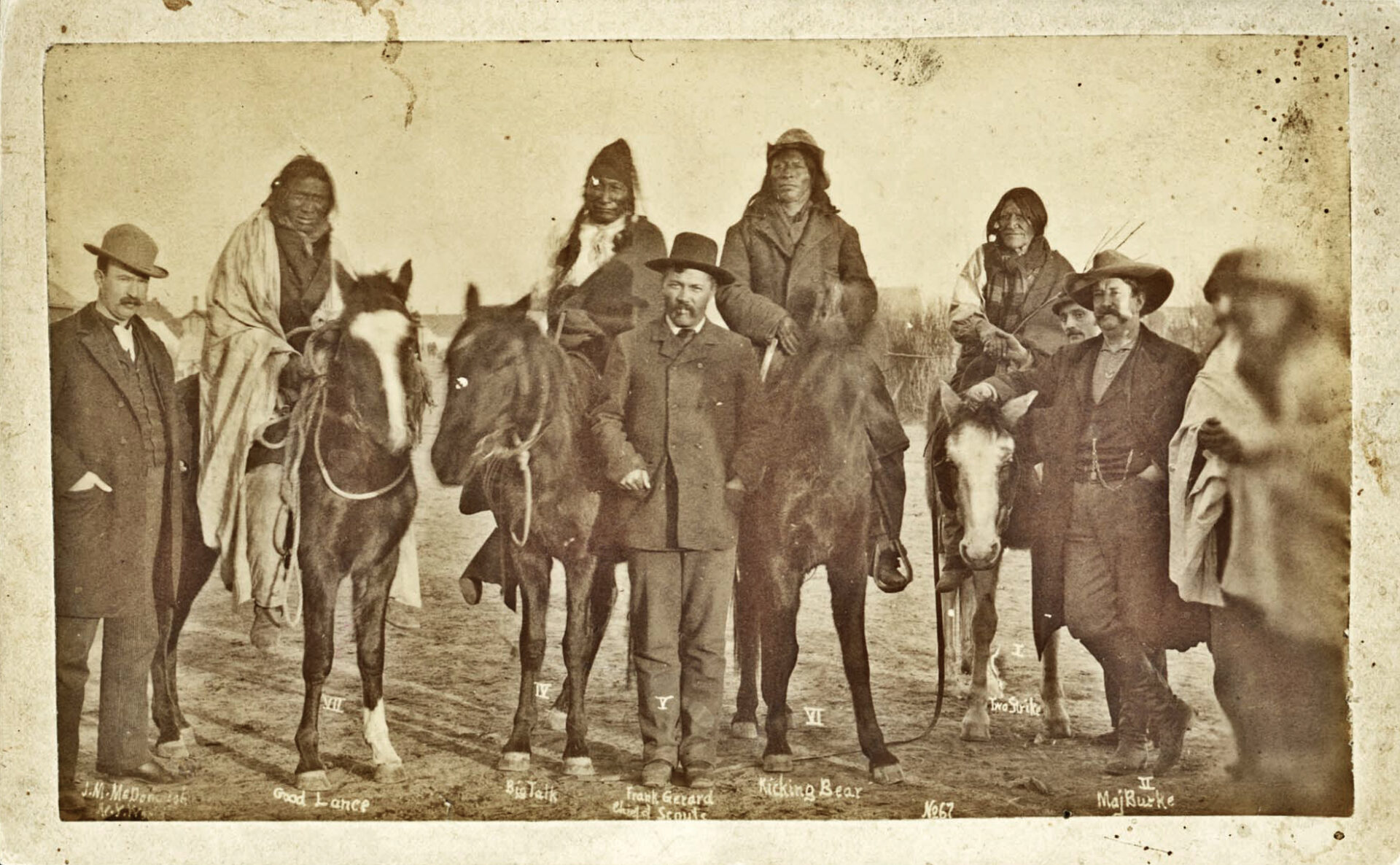

Image 1: Courtesy of History Nebraska – Members of the Santee Sioux tribe on horseback posed for this photo about 1890, several years after the Lightner family left the Santee Sioux Reservation.

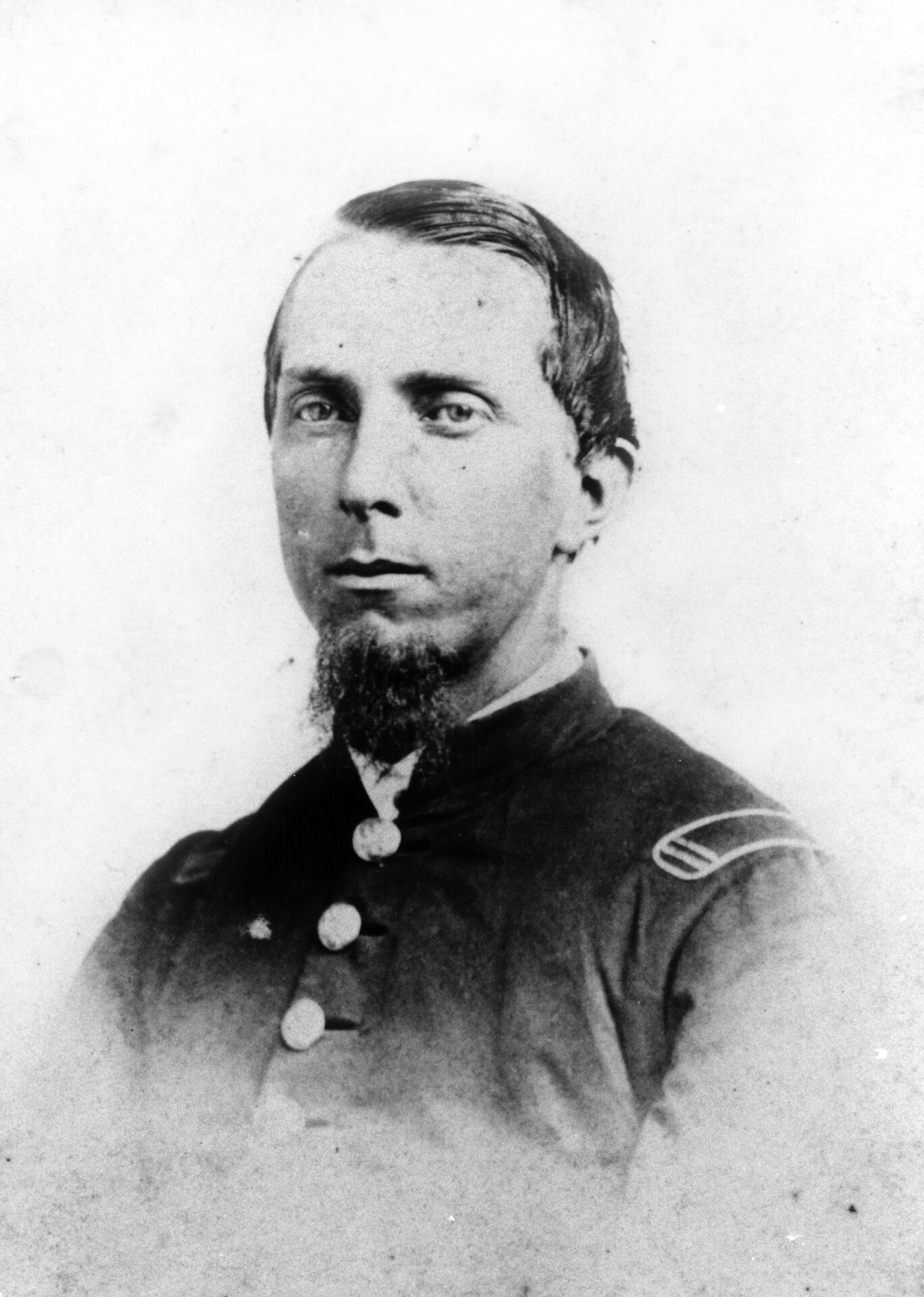

Image 2: Submitted photo – Isaiah Lightner of Union Bridge (1841-1923) served in Company F, 7th Maryland Volunteer Infantry from August 1862 until May 1865.

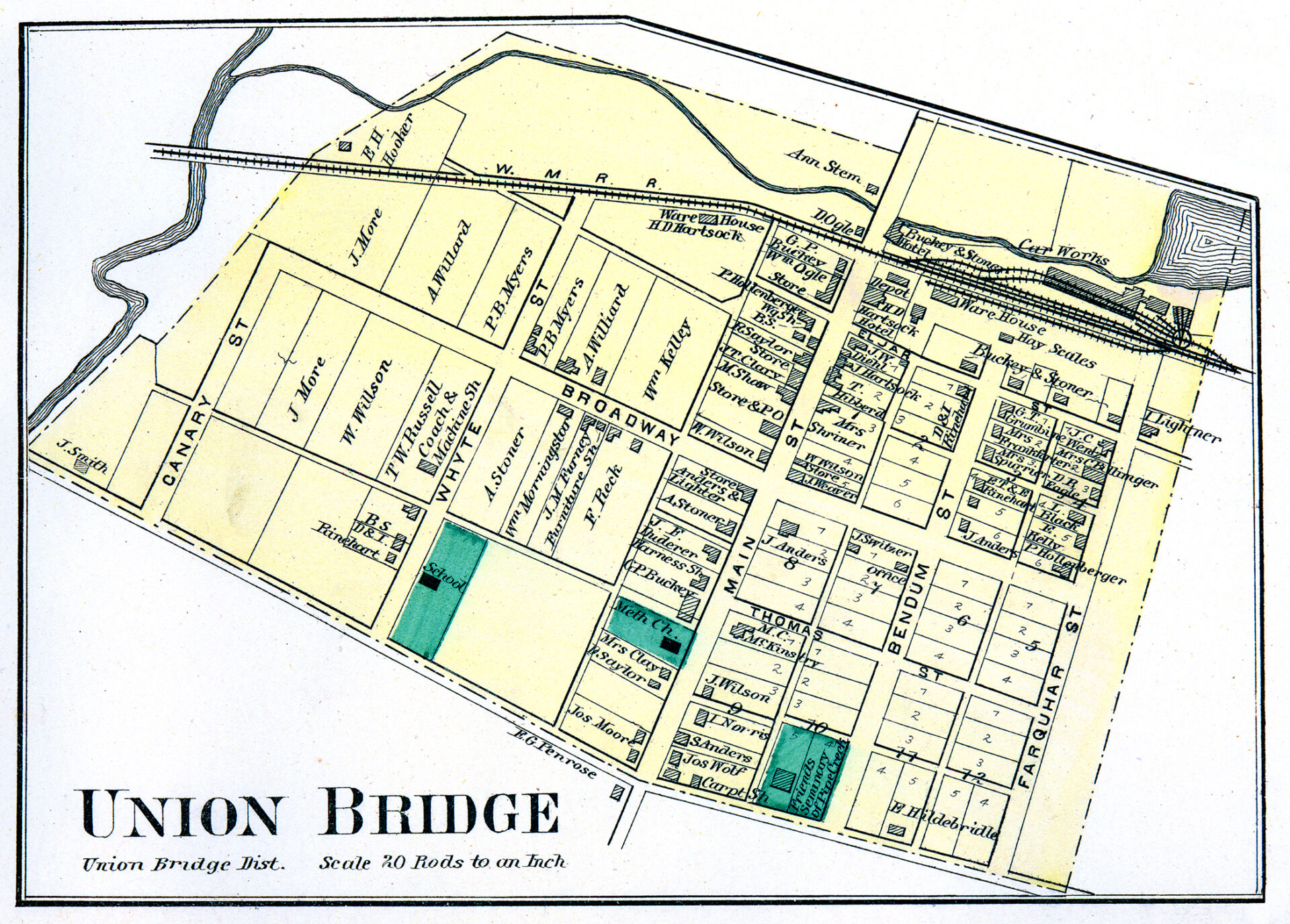

Image 3: 1877 Carroll County Atlas – On this 1877 map of Union Bridge, Isaiah Lightner’s house stands at the northern end of Farquhar Street near the Western Maryland Railroad tracks. The store he and a partner operated stood on the southwest corner of Main and Broadway. The school Isaiah and his wife helped establish was along the southernmost street that runs east-west.