Carroll Yesteryears

14 February 2021

Uncovering a Soldier’s Legacy

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

One of the intriguing stories uncovered in a search for Carroll County’s Black Civil War soldiers is that of Taneytown’s John L. Coats. While important parts of the story may always remain a mystery, quite a bit has been discovered.

When the 1850 census of Taneytown’s inhabitants was taken in November of that year, the town boasted 63 households headed by ministers, butchers, hatters, cabinetmakers, merchants, and an assortment of other occupations. Three of the households in the town proper belonged to free African Americans – the Mathews family, the Hill family, and John and Henrietta Coats’s family of six.

John Coats was listed as a laborer with real estate worth $100, probably the value of his home. He was 47 and Henrietta was 45. The four Coats children were: John L. (age 9), Henrietta (age 8), Henry (age 6), and William (age 4). If there were older children, they likely lived and worked outside the home, a common practice among low-income families.

By the time the census taker visited Taneytown in 1860, John and Henrietta still reported Henrietta as living at home plus James A. Coats, age 21, and three much younger children. John L. didn’t appear. James likely was an older son now back with his family, but John L. was living and working elsewhere as he would have been about 19. During the 10-year period between the censuses, the family’s finances improved; they now had real estate worth $600.

Newspaper articles listing the “colored men” from Taneytown who served in the Civil War referenced James A. and John L. Coats but provided few details. James A., a sergeant whose company and regiment were unknown, was killed near Petersburg; John L., a private whose company and regiment were also unknown “died since the war.” There the story stopped. Thanks to help from Dan Pyle, David Buie, and access to Civil War records, much more information came to light.

James A. Coats was working as a waiter when drafted into the 23rd United States Colored Troops in December 1863. He was promoted to 1st sergeant, killed July 30, 1864, at the Battle of the Crater near Petersburg, VA, and buried there. What about John L.?

Military records show that John Coats, sometimes spelled Cotes or Coates, didn’t wait to be drafted but joined the 2nd U.S.C.T. forming in Alexandria, Virginia, during the summer and fall of 1863. He enlisted in Baltimore, then went to Alexandria for training. The regiment’s first assignment was New Orleans and the men sailed sometime in November. New Orleans, originally a Confederate seaport, was under Union control by mid-1862 and the men of the 2nd U.S.C.T. disembarked at Fort Jackson, 70 miles down the Mississippi from the city. It was an unhealthy, swampy location; for Sergeant John L. Coats it proved an unfortunate one.

Black Louisiana troops already stationed at Fort Jackson were becoming more and more enraged over the treatment by their white officers—subjected to the kinds of punishment they had endured when they were slaves. Now they were part of the United States Army and expected to be treated in accordance with military regulations. John Coats’s unit found itself dumped into this volatile situation.

On the night of December 9, 1863, hundreds of soldiers in the 4th Infantry Regiment (Corps d’Afrique) stationed at Fort Jackson mutinied after their commanding officer, Lt. Col. Benedict, “struck and punished two soldiers with a whip” for a minor offense. As an officer, Sergeant John L. Coats had to decide whether “to observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the rules and articles for the government of the Armies of the United States” or to stand with fellow African Americans reacting to mistreatment. He chose the latter action—failing to suppress the mutiny. No lives were lost; the mutiny lasted a very short period; and General Nathaniel Banks, Commander of the Department of the Gulf, condemned the flogging but couldn’t ignore the mutinous action. Coats and others found themselves facing courts martial.

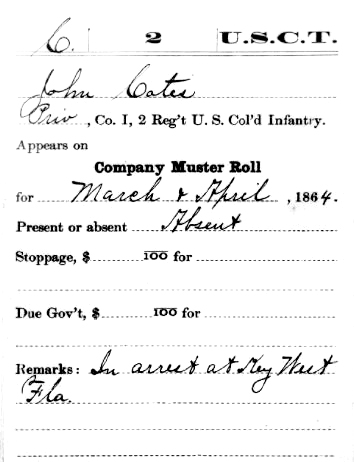

By January 1864, John Coats’s military record showed he had been arrested and reduced to the rank of private. Most likely he was also incarcerated, but went with his unit to its next assignment at Key West, Florida, where his trial took place. He faced two charges: 1) “Exciting and joining in a mutiny,” and 2) “Being present at a mutiny and not using his utmost endeavor to suppress the same.” The court found him guilty. Perhaps it was the second charge which ultimately resulted in his sentence because the flogging by Lt. Col. Benedict caused the mutiny; the men of the 4th Infantry Regiment needed no “exciting.”

The sentence, recorded in General Orders No. 13 on August 1, 1864, at the military headquarters of the District of Key West and Tortugas, read “. . . and the court does therefore sentence him, Private John Coates of Co. ‘I,’ 2 U.S.C. Troops arraigned as Sergt. of said Co. and Regt. but now a private thereof, to one year’s confinement at such place as the proper authorities may direct, fourteen days of each alternate month, to be upon a diet of bread and water, and to forfeit to the U.S. all pay, now due or to become due during the time of his confinement.”

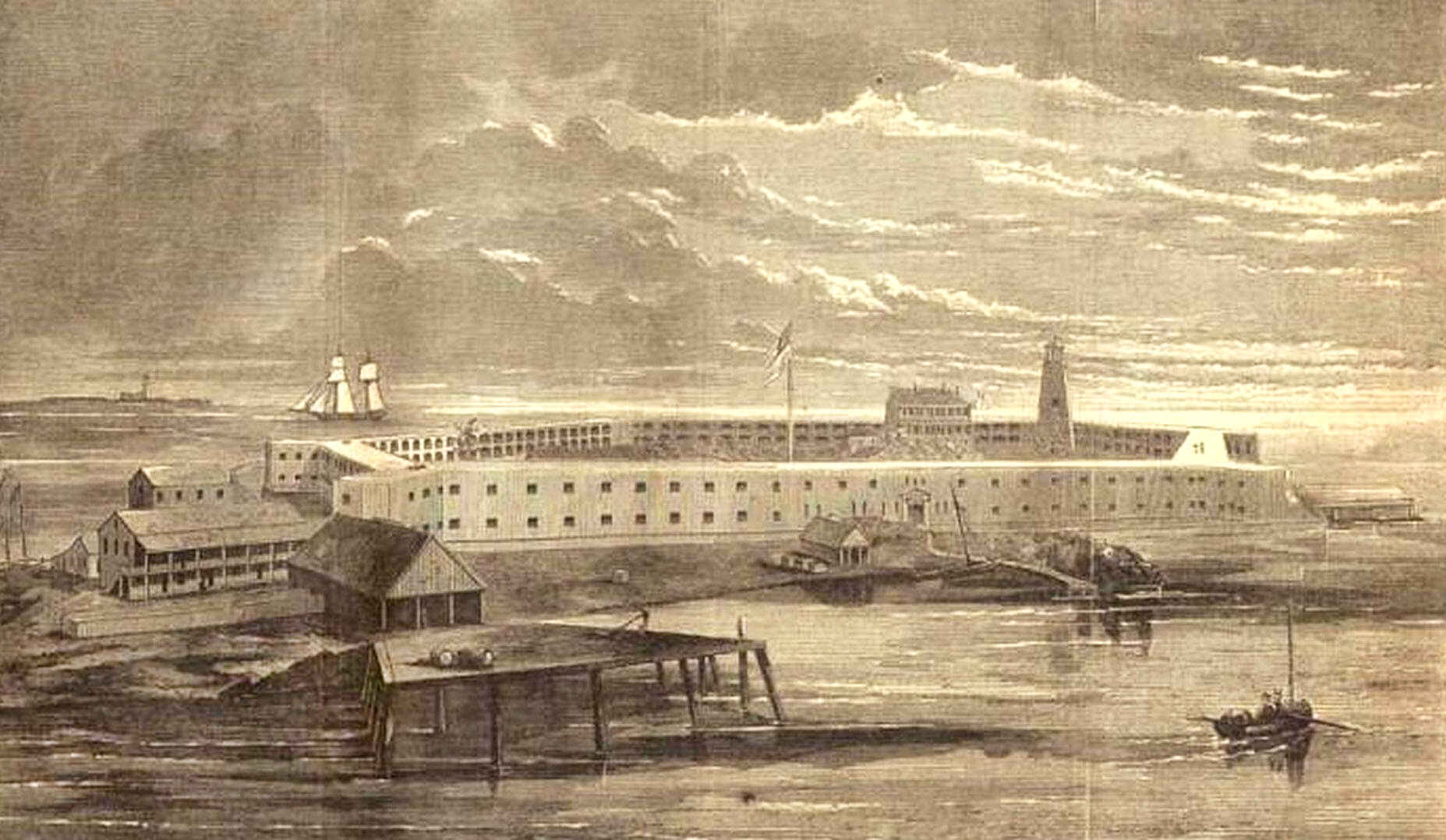

The place of confinement chosen for Coats and Henry Cornish, another member of the company also involved in the mutiny, was Fort Jefferson, a huge masonry fort on one of the islands off Key West. Cornish was to serve at hard labor at Fort Jefferson for the remainder of his enlistment; Coats was to serve for one year, then allowed to return to his regiment which remained at Key West until the men were mustered out in January 1866.

Fort Jefferson was both a military base and a prison during the Civil War. It guarded the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, thereby enforcing the Union’s naval blockade of Confederate ports along the Gulf Coast. All its supplies were delivered by ship; rainwater was collected in giant cisterns. Perhaps the fort is best remembered as the place where Dr. Samuel Mudd was imprisoned after aiding John Wilkes Booth after he assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

John L. Coats survived his year at Fort Jefferson, left the army in January 1866, and next appears in Baltimore in the 1870 census. His age was then 28. He now listed his occupation as “mariner,” and shared living quarters with Robert Mills, age 29, who may have been a Civil War veteran from Worcester County. Next door lived the family of William Bivens and his wife, Henrietta, none other than John’s sister!

The 1870 census is the last appearance of John L. Coats. William and Henrietta Bivens later moved to Taneytown where John’s parents still lived, but John L. can’t be traced further. He may have died before the 1880 census. Perhaps he was buried at St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church in Taneytown where his father was laid to rest in 1882, but there is no headstone. It would be nice to learn how the last years of his life were spent – where and when he died – but for now, this is the end of his story.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Image 1 – source – Alamy Images from Harper’s Weekly

Fort Jefferson off the coast of Key West, Florida, in 1865, the same year John Coats was serving his prison sentence for not suppressing the Fort Jackson mutiny.

Image 2 – source – National Archives

The company muster roll for “John Cotes” in March/April 1864 shows him under arrest in Key West and with the rank of private.