Carroll Yesteryears

14 April 2019

Rewriting History Appropriate to Convey Corrected Facts

By Jeff Duvall

Here is an issue which has been showing up more and more over the last few years. What if material presented as fact on the internet, in local history books, and in newspapers is actually wrong? The question becomes, do we correct it or continue to perpetuate wrong information? Facts such as the land on which a person lived, people identified in a photograph, and town, creek, or road names are a few examples that have been found to be incorrect. A recent example appeared in this column on 23 November 2018. The writer stated that Westminster had never been called Winchester and referred to William Winchester’s original map where he named his town Westminster. A different picture emerges upon looking further into the story.

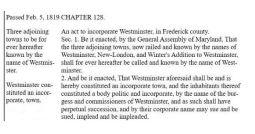

When Westminster was laid out in 1764 (Frederick County Deed L-473) it was, indeed, named Westminster by its founder. But then jump to an entry in the 1791 Laws of Maryland where Chapter 82 authorizes layout of a road “from the Baltimore county turnpike road at WinchesterTown, thru Taney-town and Emmitsburgh to the Pennsylvania line…” Jump forward another 22 years. The Maryland legislature passed a law in 1813 relating to the Westminster General Meeting House whose trustees were “sundry inhabitants of the town of Westminster, in Frederick county…” Then, in 1819, Maryland’s General Assembly decided “that the three adjoining towns, now railed and known by the names of Westminster, New-London, and Winter’s Addition to Westminster, shall for ever hereafter be called and known by the name of Westminster.”

Nevertheless, the following is what appeared in an 1898 newspaper detailing Westminster’s history: “For years it bore the name of Winchester, and would perhaps still bear it but for the fact that the name was duplicated elsewhere [Winchester, Virginia] which caused some confusion in the mails.” Am I disparaging past historians? No. If they had access to the information and the technology to retrieve it that we have today, they might have made fewer errors.

There is also the issue of making statements without sources to back them up. When writers provide no sources or documentation, or if their sources date to a bygone era, this should raise a red flag. Nobody likes to be told he is wrong and some people take more offense than others. The bottom line is—do you want to convey correct information?

Don’t dismiss all early material. Use it as a starting point. Can what those early writers said be proved or not? Expand your search if various sources contradict each other. Make use of your local library and historical society. They contain so much information not widely available. One day all of their material will be available electronically, but for now plan a road trip and see how many times you will be surprised at what you can discover. Take the time to research an issue and if no direct information is found, don’t jump to a conclusion. Allow others to decide for themselves or continue researching. No one person has all the answers. Clues lead to additional areas to check that you may know nothing about. Guest columnist Jeff Duvall has deep roots in Carroll County and enjoys researching local history and land records.

Image source: Submitted image

Image caption: This excerpt from the Laws of Maryland passed by the Maryland General

Assembly in 1819 shows an official naming of Westminster while it was still part of Frederick