Carroll Yesteryears

30 December 2007

19th Century Holiday Sales

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Did your family receive an HDTV from Santa this Christmas? Perhaps you gave someone a cell phone, wrapped a box of Legos for a grandchild or sent an Amazon gift certificate to a person who was hard to please. Whatever you gave or received, it likely was quite different from the presents of long ago.

According to an Internet source, the average annual wage for manufacturing workers in the U.S. in 1900 was about $435, or roughly $8.37 per week, so many families watched their pennies as they bought gifts and planned their holiday entertaining.

Looking at Westminster newspaper advertisements from the 1890s, you are first struck with the fact that merchants didn’t start promoting holiday merchandise until December. Theo. Derr & Son offered dress goods, coats and wraps for ladies and children, shoes, hosiery and underwear “all at Special Prices for Christmas Week.” This firm wasn’t luring customers into the store with bargains which began weeks or months ahead of time. In addition to clothing, it suggested gifts of down pillows, muffs and furs, carpet sweepers and silk or linen handkerchiefs. A husband who couldn’t afford both might be left with the dilemma of buying his wife either a carpet sweeper or a muff!

Derr’s advertisement also mentioned “Japanese Art Goods, this line includes many beautiful presents, all useful and ornamental.” Was Japan supplying the U.S. with the kinds of articles which China does today? Did the bases of ceramic knick-knacks read “Made in Japan” during that era?

Matthews & Myers, located at 45 East Main Street “nearly opposite Catholic Church,” politely encouraged holiday shoppers in 1893 with the invitation, “Our Prices are no higher at this season, and it will pay you to examine our Beautiful Selection if you wish to buy.” The firm carried etchings, pastels, engravings and photo frames along with albums, toilet cases, manicure sets and a complete line of novelties.

A jewelry store owned by A. H. Wentz offered gold and silver watches, glasses, and “everything in the jeweler’s line.” U.L. Reaver’s shop sold “boots, shoes, hats, trunks, valises and umbrellas, suitable for holiday presents.” Prof. John T. Royer was the source for musical instruments and sheet music while A. C. Strasburger sold luxury items such as fine whiskies, wines, brandies, tobacco and cigars.

Parents could purchase a 20-inch doll with kid body, bisque head, shoes and stockings, long hair and teeth for 99 cents, reduced from $1.50, or pay 10 cents for a bean bag game or 4 cents for a child’s book. The nineteenth century equivalent of a video game was probably the “magic lantern with 30 views” which cost 35 cents.

John J. Reese’s grocery store was a source for anyone who gave delicacies as gifts. His selection of fruits, nuts and candies would make most mouths water. Figs were 10-15 cents per pound; almonds, English walnuts and mixed nuts were 15 cents a pound and 7 O’clock coffee cost 25 cents. If you decided to make mince meat pies, the filling cost 12 ½ cents a pound. Oranges or other fruit could be purchased to put in Christmas stockings. Mr. Reese also carried hams, spices, molasses and other staples for holiday cooking.

Although grocery stores like that of John Reese didn’t advertise turkeys, an 1893 ad showed they were selling for 10 cents a pound and chickens cost about a penny less. Eggs averaged 25 cents a dozen; butter was approximately the same per pound.

Stop a minute to figure how far you could have stretched your weekly paycheck about 100 years ago to put presents under the tree and Christmas dinner on the table!

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

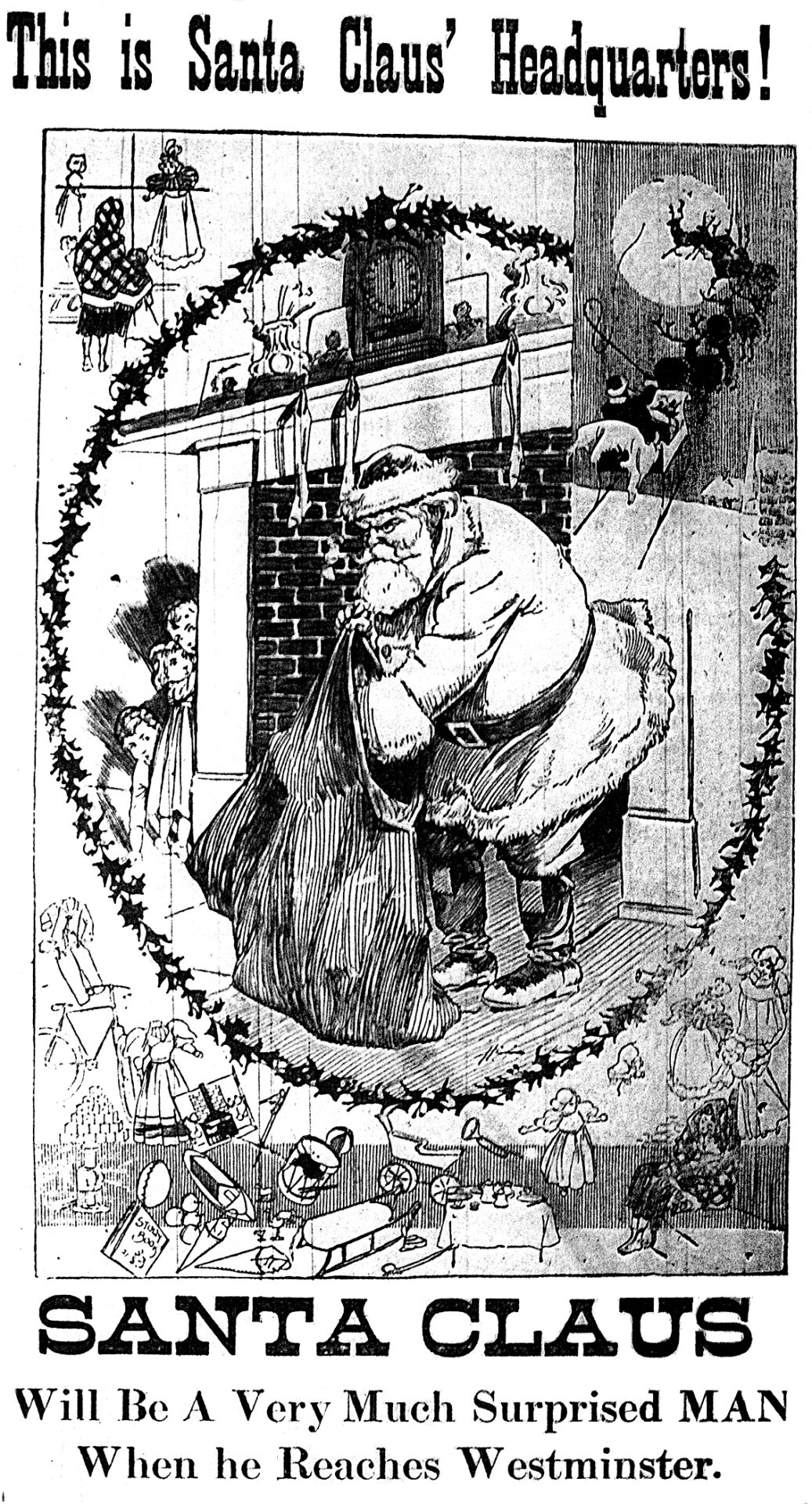

Photo caption: Miller Bros. Store in Westminster envisioned a role as “Santa Claus” in this December 1899 advertisement from the American Sentinel newspaper.