Carroll Yesteryears

26 June 2011

Carroll Turned to POWs During WWII Labor Shortage

by Mary Ann Ashcraft

As America sent millions of her young men off to fight in World War II, the shortage of manpower became more and more critical here at home. Although women went to work in many industries, there were simply not enough of them nor were they physically capable of filling all the labor needs. The Times ran a photograph on June 18, 1943, with the caption, “Wanted: 3,500,000 Extra Farm Workers.”

By June 1944, significant numbers of German prisoners had been captured in the European Theatre and some of them were incarcerated at Maryland’s Fort Meade. Under the 1929 Geneva Prisoner of War Convention, it was permissible for “detaining nations” to benefit from “the production labor of enlisted prisoners.” Here lay an answer to Carroll County’s overwhelming need for farm workers that year.

A prisoner-of-war camp was set up in the woods near the present-day Wakefield Valley Golf Course outside Westminster where approximately 300 German prisoners, under guard, were housed in tents. Initially, the men were brought in to “work for Carroll county canneries and for Baltimore city packing houses which have viners in Carroll and Baltimore counties.” However, they stayed longer, working not only for farmers and canners but other employers as well.

Before using POW labor, an employer had to prove there was “no free American labor available for the project.” Once permission was obtained, prisoners worked eight-hour days six days a week. Each detail of 8-10 men was accompanied by a guard and the men had to work close enough that they were all constantly within sight. Their wages were sent to the U. S. Treasury, but each man was allowed 80 cents per day by the War Department – enough to furnish him with stationery, stamps and cigarettes at 1944 prices.

Dr. William Zinkham’s family owned a 150-acre farm outside Taneytown during the war and he distinctly remembers his father employed prisoners of war on special occasions like threshing days. The men were “good workers,” he recalled. His mother, Helena Lang Zinkham, had emigrated from Germany as a 12-year-old girl, so she could converse easily with the prisoners and help them with letter-writing. Although employers weren’t required to feed the POWs, men employed on the Zinkham farm came inside for refreshment of some sort, and Helena’s home-baked bread was greatly appreciated.

Near the end of the war, Virginia Ecker Hierstetter’s father needed a new septic system for his house on the Old Westminster Pike. He called a plumber who brought approximately eight POWs to do the digging. Helen Shriver Riley speaks of German prisoners who helped in her family’s large canning operation.

POW camps were also set up in agricultural areas of southern Pennsylvania such as Gettysburg and Stewartstown during the summer of 1944. Since the prisoners were housed in tents, it can be assumed they were returned to Fort Meade or another army base once harvesting was over and cold weather set in.

A German mother must have counted her blessings if she received letters from a son confined to a POW camp in Carroll County in 1944.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

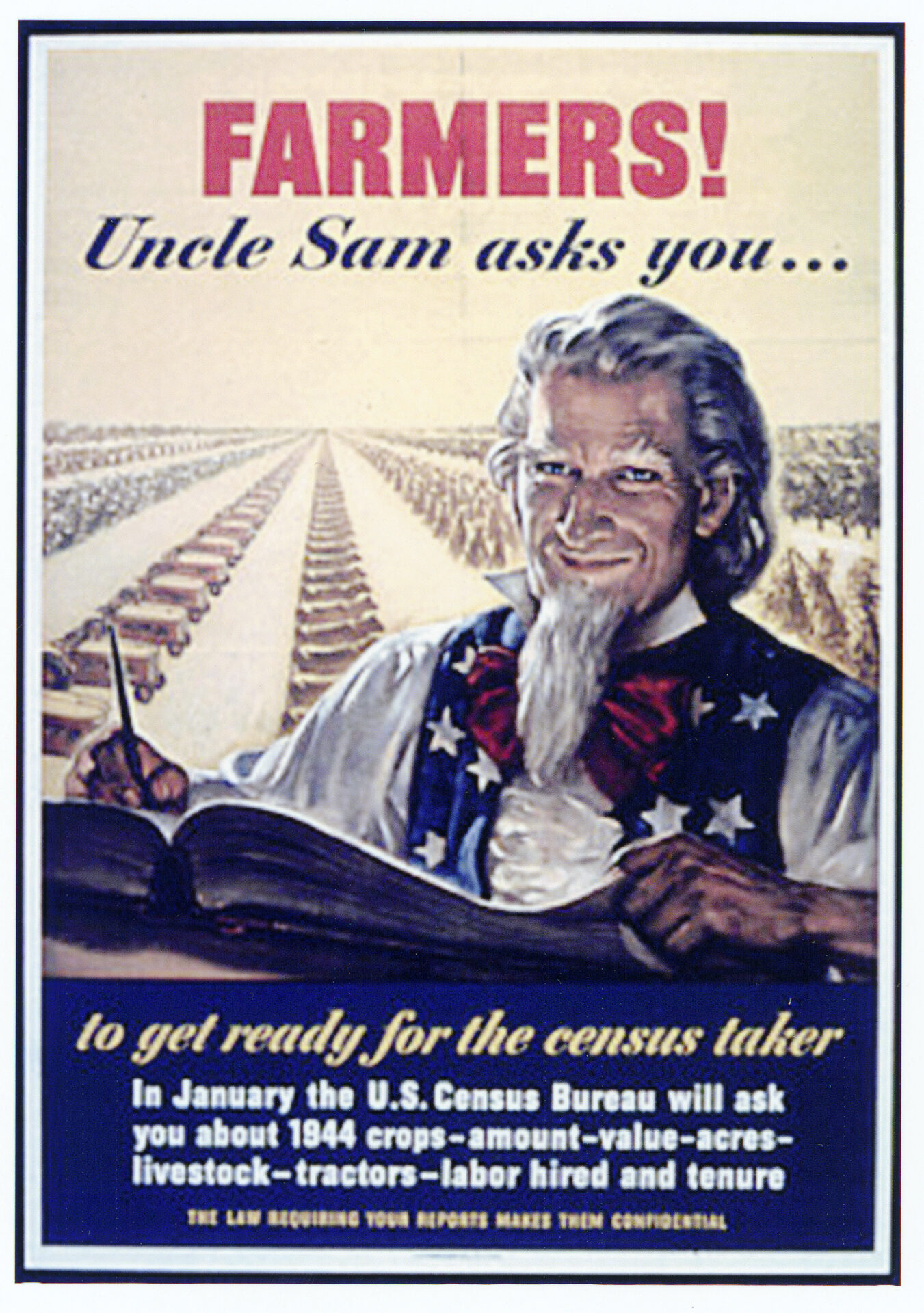

Photo credit: U. S. National Archives

Photo caption: Posters such as this were widely distributed during World War II and used to address a variety of important issues. Other examples can be found on the National Archives website.