Carroll Yesteryears

26 October 2014

A Soldier’s Account of the Battle of Bladensburg

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

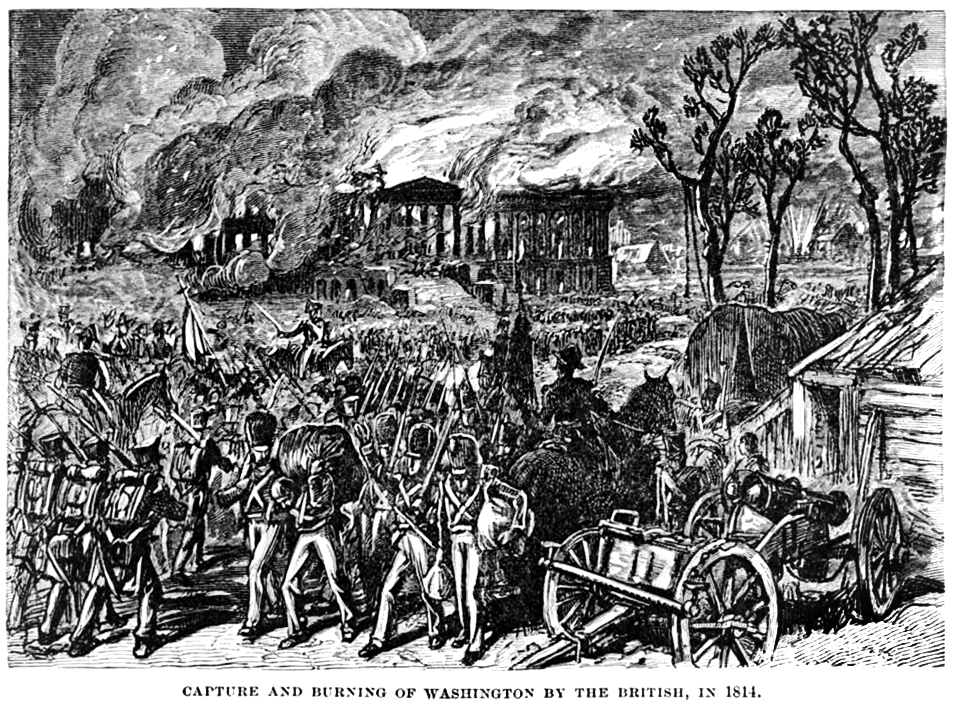

Marylanders were proud of the glorious American victory at the Battle of Baltimore in September 1814. It was a far better showing than what occurred the previous month when the British routed our troops at the Battle of Bladensburg (MD) and burned Washington.

The Historical Society of Carroll County recently received a copy of a letter written September 9, 1814, by Lieut. George W. Hoffman to his father, John. Hoping to defend his actions and those of others who scattered before the British assault, he described their roles at Bladensburg, a battle often called “the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms.”

Hoffman’s letter paints a picture of untested local militiamen who marched in the August heat from Baltimore to Bladensburg, a village northeast of Washington, to intercept British forces recently landed along the Patuxent River. Bladensburg was considered a good location to confront an enemy that might attack Baltimore, Annapolis, or Washington.

From the very beginning, things didn’t go well. Before a single British soldier appeared, a friendly-fire incident at Bladensburg resulted in the deaths of two men in the company next to Hoffman’s. The American troops had scarcely left the village on a march toward Upper Marlboro when they received orders to turn around. Hoffman and his men camped the night of August 23 with empty stomachs except for watermelons eaten around midnight. Long before dawn on the 24th, they arose and began a new march, this time toward Washington, but when they were within three miles of the city, they were ordered back to Bladensburg once again. By the time they returned, the men were so hungry they “began to break the line before we were dismissed to get the apples off the trees.”

August 24 wore on with Hoffman’s company awaiting its next orders. Soon, uniformed men appeared in the distance. They turned out to be American troops rushing in from Annapolis with the British hot on their heels. Finally, roughly 7,000 Americans arranged themselves in line of battle and the fight began. As the first smoke from cannons and muskets began clearing, Hoffman observed chaos in the American ranks. He cried, “Form, form” to those around him, but his efforts and those of others failed to rally the troops. “When the men found that the enemy were advancing and being all in confusion nothing could be done, and they all broke off again, and faint with fatigue as I was from the days before, and hungry together with calling out to the men so much that my mouth became quite dry, I was fit to despair …”

Young Hoffman considered surrender, then decided to escape and live to fight another day. Nine members of his company eventually reached Rockville. In the distance, they had witnessed American troops leaving the Washington Navy Yard after setting it afire to prevent its capture and had “plainly seen the capitol and Presidents house on fire.”

Thinking about a future opportunity to revenge the defeat, Hoffman wrote, “I will be satisfied, hoping that victory may Crown us or that I may not be sensible of our disgrace…”

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Photo caption: This wood engraving from 1876 depicts the burning of Washington by the British in 1814.