Carroll Yesteryears

8 November 2009

Child Apprentices Once Common

by Mary Ann Ashcraft

Among the fascinating records at the Carroll County Courthouse is a fragile, handwritten ledger with the title “Book of Indentures.” It covers indentures from the county’s founding in 1837 until 1927 when the last entry was the placement of a four year-old girl, born out of wedlock, whose mother was dead and whose father was unknown. What was the indenture process and what purpose did it serve in the past?

Ancestors of many Americans arrived in this country as indentured servants – indebted to the person who paid for their passage across the Atlantic and obligated to work for that person until the debt was paid. However, the indentures recorded in the Carroll County ledger were of a different sort. They were legal agreements to apprentice children to a master or mistress in order to learn a trade. Sometimes the person signing the agreement might be a parent; sometimes it was local Justices of the Peace arranging for the care of an orphan or the child of someone living at public expense in the county alms house.

Studying the records, it appears the indentures fall roughly into two categories. A number of teenagers were apprenticed to specific tradesmen such as printers, shoemakers, millwrights or blacksmiths. These apprentices were old enough to actually learn a craft and perhaps had shown some aptitude for it. The other indentures were often made when children were under ten years of age. In such cases, the boys were usually to learn farming and the girls to learn housekeeping.

Poverty must have motivated the parent who indentured a child that young. Who would not want to see his child better fed, wearing warmer clothing, and given more opportunity to succeed. With new babies often arriving every two years, a poor family might find indenturing one or two children a heartbreaking but necessary solution to their problems.

The written agreement between master and apprentice could be general or quite specific. The apprentice must show respect for the family, “not waste the goods of his master,” not marry, “not drink or swear on any account,” and generally conduct himself properly while living in the master’s household. For his part, the master should provide adequate food, clothing, lodging, washing, and some basic education plus instruction in the “art, trade and mystery” of an occupation. When the term of indenture was over (usually at age 21 for boys and 16 or 18 for girls), the apprentice left with two new sets of clothing and, perhaps, money.

John Coker apprenticed his seven year-old daughter Susannah to learn housework and plain sewing in 1838. His agreement with John Orendorf stipulated that at the end of her indenture she would receive “one good new spinning wheel, one new Bedstead, and bed clothing” as well as other items.

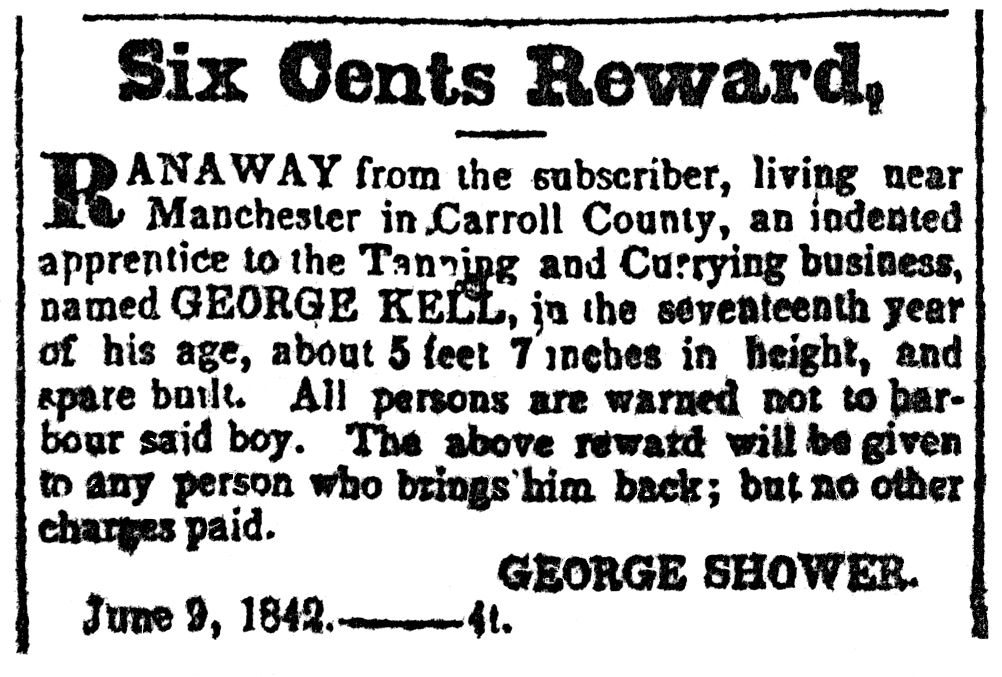

Of course not all masters or mistresses were kind and considerate nor all apprentices respectful. Either party could take grievances to the Orphans’ Court for a hearing and some agreements were dissolved for very good reasons. George Kell, the apprentice in the accompanying advertisement, apparently decided to simply run away.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Submitted photo

Photo caption: This advertisement for a runaway apprentice appeared in an 1842 Carroll County newspaper. Did George Shower’s six-cent reward reflect his opinion of the young man’s worth?