Carroll Yesteryears

9 March 2014

Scarlet Fever Struck Silver Run in 1877

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Mother Nature has thrown lots of nasty weather at us during the past few months, but we are lucky that this hasn’t been a year when cases of the flu have been prevalent. That’s a relief!

Wandering through St. Mary’s Cemetery in Silver Run several years ago, I encountered a row of headstones for members of the Kesselring family which lived in the town in the 1870s. Looking closely, I realized that Samuel Kesselring lost five of his children, three daughters and two sons, between March 29 and April 2, 1877. These weren’t youngsters. The oldest was 23 and the youngest 12 – well past the age when disease carried off so many children during that era. What was going on? The answer appeared in the April 7, 1877 Democratic Advocate newspaper – there was a scarlet fever epidemic in the town.

When I was growing up in the 1940s, you occasionally saw signs on doors announcing that the house was quarantined because someone had scarlet fever. Nobody was supposed to enter. It was a disease which struck fear in everyone until antibiotics became widely available. In 1877, the doctor who visited Samuel Kesselring’s house would not have been able to cure it with any medicine in the little black bag he carried in his horse-drawn buggy.

Scarlet fever was usually a childhood disease, but the Kesselring children were well beyond the normal age to succumb to it. Fortunately, at least one child in the family survived, but we don’t know whether he caught the disease or not. He was almost the same age as the other children. What affected the family must have been a very virulent strain of the Streptococcus bacterium, or perhaps the children were weakened by something else. Who can imagine the suffering during that final week of March 1877 and in the years after when Samuel and his wife thought back on the events and visited the children’s graves.

In researching scarlet fever for this article, I found that Thomas Edison probably survived the disease as did Helen Keller, although that is likely what caused her to completely lose both her vision and hearing. It sometimes caused rheumatic fever which left people with weakened hearts and it affected the kidneys as well. We don’t have a vaccine to prevent scarlet fever, but today’s antibiotics keep it from being the scourge it once was.

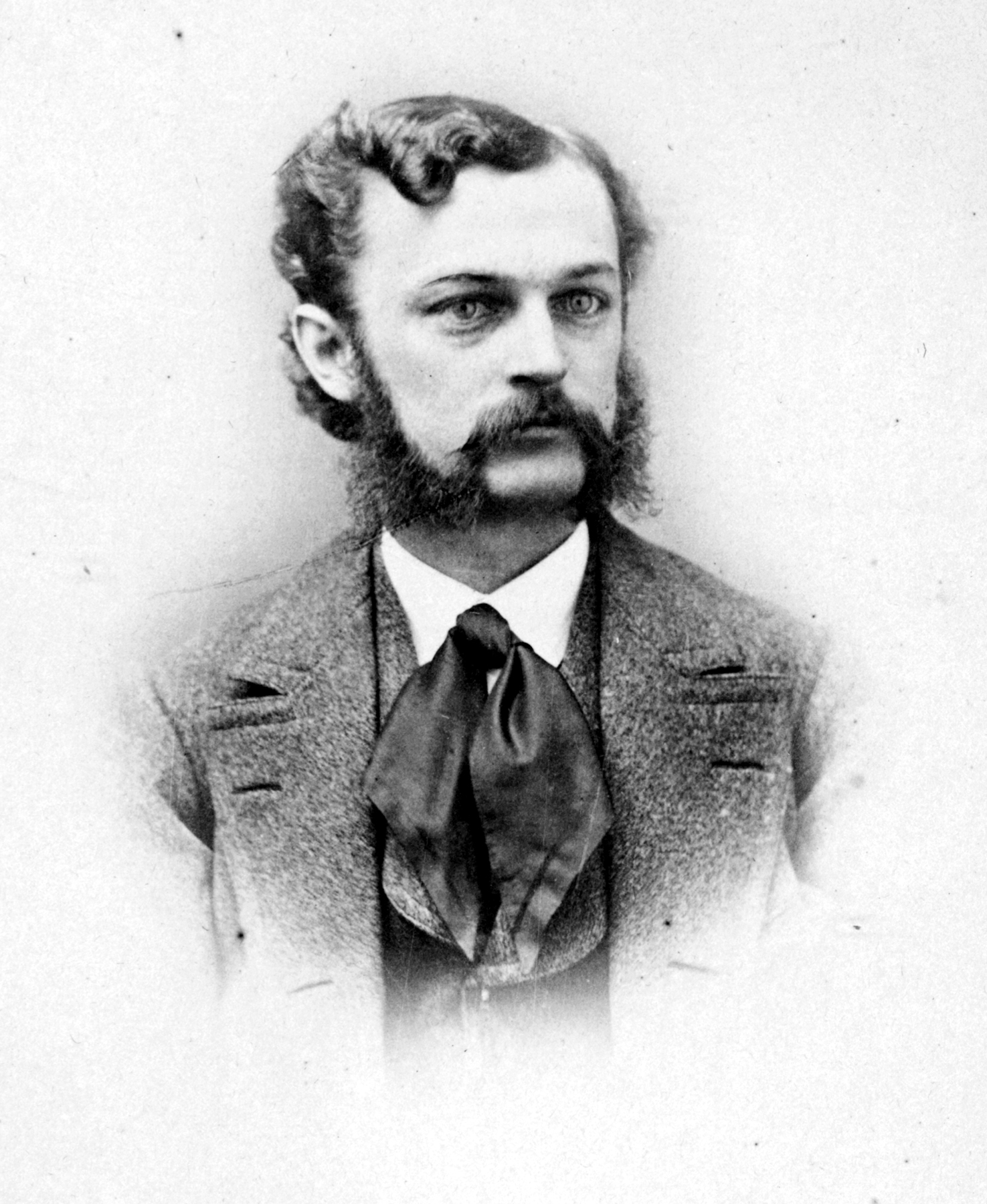

The inhabitants of Silver Run in the 1870s could call upon at least one local doctor as well as others who traveled from Westminster, Uniontown, or the Hampstead/Manchester area. Dr. Daniel Coonan lived in Mt. Pleasant, a village south of Union Mills and north of Westminster. He was an 1866 graduate of the University of Maryland Medical School. Other nearby doctors were Wm. N. Martin and the J. J. Weavers, a father and son practice. All three lived in Uniontown but served the sick in surrounding communities. The University of Maryland Medical School, one of the earliest in the U.S., supplied Carroll County with a number of its physicians during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo caption: Dr. Jacob J. Weaver, Sr. and his son, Jacob J. Weaver, Jr., practiced medicine from Uniontown over the course of four decades. This photo, probably taken in the 1870s, shows Dr. Jacob J. Weaver, Jr.