Carroll Yesteryears

14 February 2016

Brick Making in Carroll County

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

You might become suspicious when looking at the large number of old brick buildings in Carroll County that someone local must have had a clay pit and produced bricks. Sure enough, an article entitled “Brickmaking in Westminster” appeared in the Democratic Advocate of May 10, 1888, and it sheds light on an industry that has disappeared.

Beginning in 1881, R. Charles Matthews operated a thriving business making and selling bricks along Railroad Avenue north of Westminster’s city limits. His clay came from a nearby meadow which he leased from Theodore Englar, and the plant’s proximity to the Western Maryland Railroad was ideal for sending bricks to other locales.

Approximately 200,000 bricks were produced during the first year of operation, but by 1886 the number had risen to almost three-quarters of a million. Of course weather played a part in each season’s success because the bricks needed to dry before being fired. Apparently in 1887 the weather didn’t cooperate and Matthews had to enlist the help of other local brick manufacturers to fill the orders builders had placed.

William Oursler, Wm. H. Bell and Robert E. Frizzle added over 200,000 bricks from their supplies to help Matthews deliver what he had promised. An 1877 map of Westminster from the Lake, Griffing, and Stevenson Illustrated Atlas of Carroll County pinpoints the location of Bell’s brickyard near the intersection of Church and East Green Streets in Westminster. An 1887 newspaper advertisement showed Frizzle’s brickyard was on Court Street near the county jail.

The location of Oursler’s yard is unknown, but was probably in the vicinity of Westminster as well. Matthews’ brickyard was quite close to John K. Longwell’s lovely mansion “Emerald Hill” which stood above Westminster’s East Main Street. In the twenty-first century, it is hard to imagine that these rather “dirty” industries often flourished alongside residential areas in many towns and cities.

The entire process of brickmaking took place close to downtown Westminster—digging the clay, grinding and tempering it, sanding the molds, molding the bricks, drying them and loading them into the kiln for firing. According to the newspaper, Matthews employed a large number of men and had plans to open a second brickyard east of Westminster at Carrollton Station on the Western Maryland Railroad so he could produce as many as a million bricks a year.

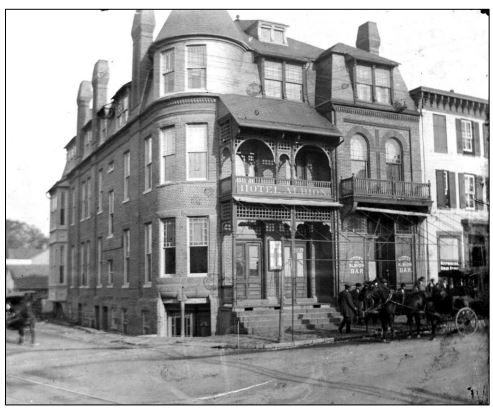

Matthews’ advertisement in an 1887 Westminster newspaper said, “If you want to see the kind of wall my Brick will build, just take a look at the new Hotel Albion or the First National Bank, Ward Hall [at Western Maryland College], J. Q. Stitely’s double house on Green street, or C. Awalt’s block of houses.” Some Carroll County schoolhouses and at least one barn were also built of Matthews’ bricks, and he shipped bricks to Baltimore for homes on Pennsylvania

Avenue, Patterson Avenue and near Druid Hill Park. Like so many other industries—flour mills, distilleries, ice-making plants, etc.—that flourished in the heart of Westminster, the brickyard disappeared. Today, there is a plant in Rocky Ridge on the eastern side of Frederick County which produces large quantities of fine bricks.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo credit: Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo caption: The Albion Hotel, seen here before its brick walls were painted, was built in the 1880s using locally manufactured bricks. It stands on the northeast corner of the intersection of Westminster’s Main Street and Railroad Avenue and today is home to several businesses on the ground floor and apartments above.