Carroll Yesteryears

23 April 2017

Issues Involving Schools as Old as Schooling in Carroll

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Issues concerning Carroll County public schools have appeared in this newspaper’s headlines quite often recently. The problems of today aren’t very different from those of the past—too many students or not enough, low teacher salaries, buildings in poor repair, insufficient budgets, etc. Let’s look at what school board minutes and newspapers from the late 19th century have to say.

In September 1882, 53 teachers protesting their salaries signed a petition addressed to Carroll’s Board of Public School Commissioners that was published in the Democratic Advocate. Although they represented only about one-third of the teachers that year, it took courage to put your name on a petition, and those who signed undoubtedly were justified. The petition said, “We have read in the public prints, with feelings akin to dismay, your determination to reduce during the coming school year, our previously meagre and insufficient salaries.” The teachers also mentioned a lower salary would “limit our powers for usefulness in our schools as it contracts our means of living.” The school commissioners constantly faced budget shortfalls, but teachers’ salaries hardly differed from what a common laborer made during the same period. When you were single-handedly expected to control and teach a roomful of students ages six to eighteen, who could blame the teachers for protesting. On the other side of the issue was the dilemma faced by commissioners who never received enough money from the State or from local taxes to operate schools scattered across the county.

In 1883, there were 132 of them. With no system of public transportation for students, schools had to be within walking distance. As Carroll’s population grew, parents constantly approached the commissioners asking for schools to serve their areas. That sent the commissioners to local banks for loans to keep the schools going, and interest on those loans then became part of the next year’s budget. There was another issue which didn’t help matters. Carroll’s schools were segregated which meant operating separate schools for children who sometimes lived next door to each other – hiring more teachers and maintaining more schools. The Manchester Election District had 16 schools in 1883 ranging from larger ones in the town to little ones in less populated areas. Westminster District had 18 schools and Union Bridge had six, but there were nine other election districts with their share of schools. Each school had three

trustees assigned to look after it and help the teacher. The trustees lived nearby so they could easily keep an eye on things. Since many of the teachers were young and single, they may have boarded with the trustees and their families.

It isn’t surprising that the county began consolidating schools about 1917 and the one-room schoolhouses were sold off gradually. The consolidation process continued steadily until Harney, in the extreme northwestern part of the county, was the only community left with its own tiny school by the 1950s.

Names like Morelock Schoolhouse Road on the route between Westminster and Uniontown or Blacks School House Road off Maryland Route 97 near the Pennsylvania Line are reminders of the era of one-room schools.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Submitted photo

Submitted photo

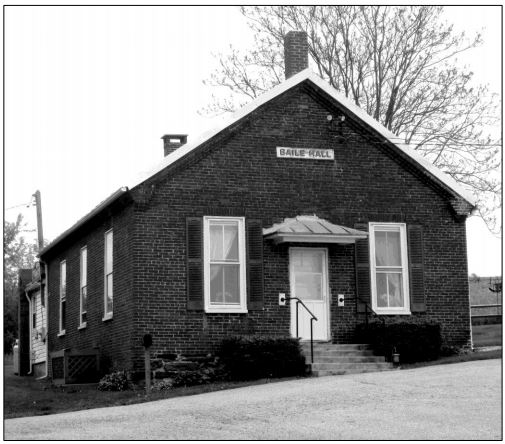

Photo caption: Baile Hall, now used by Sam’s Creek Church of the Brethren on Marston Road, was typical of Carroll’s 19th century one-room schools. It’s surprising how many former schools still exist, but they may be difficult to recognize.