Carroll Yesteryears

24 September 2017

Shoemaker’s fascinating ledger gives glimpse into Carroll from 1787 to 1814

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Shoemaker by Trade is a fascinating book recently donated to the Historical Society by its compiler, Kathleen Ann Cornwall, a descendant of the shoemaker Jacob Knibbel, later spelled Knipple. In the late 1700s, the German-speaking Knibbel lived and worked in Bachman Valley in the north-central part of today’s Carroll County. He kept a ledger recording the shoes he made or resoled for people in his neighborhood. Like other craftsmen, he apparently augmented his living as a shoemaker with other work for the those in the community, and kept track of the various

jobs in his ledger.

There are so many interesting bits of history to be gleaned from the pages of this book covering the years 1787 to 1814 when Jacob Knibbel worked here. Little is revealed about his own family; most is about his customers. First, there are the surnames that appear—ones still found in the county: Lippy, Sterner, Baumgardner, Bachman, Wentz, Bixler, Zepp, and many others. These were not always spelled the way they are today, but are definitely recognizable. When a

customer was a married woman, Knibbel spelled her surname in the typical German way by adding a feminine ending “in” or “en.” Catherine Zepp was listed as Katarana Zeppen in 1808 and Cotharena Zeppen in 1809. On June 23, 1808, Knibbel recorded that Mrs. Zepp owed him 3 pounds, 16 shillings, and 6 pence to cover nine new pairs of shoes, resoling four pairs, mowing some crops, cutting wood, and making a small door. I don’t know anything about Mrs. Zepp, but am guessing that she might have been a widow left with quite a few children who needed shoes, and she sought Knibbel’s help with farm work and chopping wood. Three years later, Mrs. Zepp was still a customer in need of shoes and help with mowing, but she appears to have paid off her previous debt.

Although the U.S. Treasury Department was established in 1789 and likely began producing U.S. currency, Knibbel recorded the sums in his ledger using the British monetary system as late as 1814. Did his customers pay in U.S. currency, in British, or were most payments made some other way? Perhaps Mrs. Zepp exchanged chickens and eggs, cow’s milk, use of a farm wagon, or some other commodity in return for Knibbel’s shoes and labor in her fields.

Kathleen Cornwall used Ohioan Josiah Beachey who was acquainted with the German dialects from our area in the 18th and 19th centuries to translate the handwritten ledger. Looking at photographs of the pages, you can appreciate the serious challenges he faced. The ledger was not in good condition; the surnames were local ones; and given names included what must have been nicknames. While it is easy to interpret Fridrich Bachman or Henrih Lipi, what about Feldi Erhardt or Stoffel Knibbeil? It turns out that Feldi was short for Valentine and Stoffel for

Christopher. Who would have guessed? Several years ago, this column featured the ledger of Emanuel Brower, a New Windsor tavern keeper. Both ledgers have become important additions to the social history of Carroll County.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

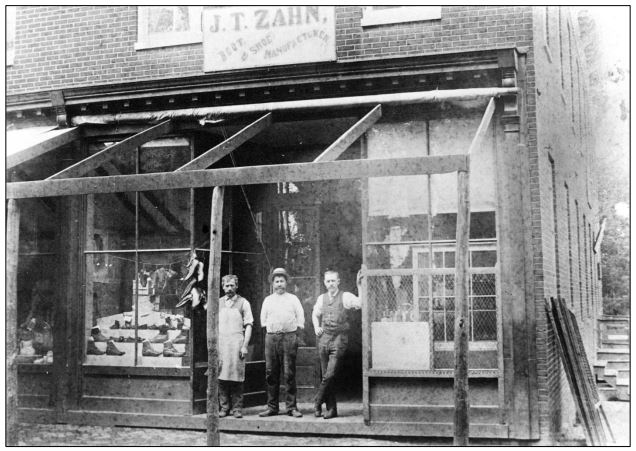

Photo credit: Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo caption: Approximately 100 years after Jacob Knibbel made shoes near Bachman Mills, John T. Zahn operated this shop at 201 East Main Street, Westminster. He stands on the right with John Beaver, a gravestone carver, middle, and Charles Stonesifer, at left. The building still stands.