Carroll Yesteryears

22 May 2016

Some Carroll-based Ancestors Can be a Puzzle

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Are you one of the growing number of people searching for your ancestors? Genealogy/family history has become a very popular hobby, and it is easier now than ever to trace your family with the resources available on the internet. However, there are usually some people in everyone’s search who seem to have fallen between the cracks. These challenges to researchers are often called “brick walls.”

At a recent Carroll County Genealogical Society meeting, the speaker’s topic was “Practical Use of the Mighty FAN Club: The Case of a Shadowy Female.” The talk offered tips on tracking women by searching for their F (friends), A (associates), and N (neighbors). Most genealogists have more difficulty finding women than men for a wide variety of reasons, often the laws affecting women in the past. However, if your ancestor was poor, he or she may have slipped between the cracks for other reasons – didn’t own property, never made a will or had any possessions at death, never had a tombstone because it was too expensive for the family, perhaps never got in trouble so wasn’t mentioned in newspapers.

In Carroll County’s published financial records, you can find the names of individuals in this category – those who were paupers. You may have no clue why they fell on hard times, but the death of the father of eight to ten children quickly sent his widow on a path to poverty, or a house burned, or the breadwinner was maimed in an accident. Records show Carroll’s government provided some degree of help and left behind the names of those who received it. One of them might be your missing ancestor. Below are some examples dating to the 1850s and 1860s.

William Delphy received $50 from the county’s coffers for “attending on a certain William F. Magee during a spell of sickness of 13 weeks duration.” Was “old Mrs. Wagner” the last in her family when she died in 1858? She was a pauper, and the county paid Samuel Wampler $2 to dig her grave. It also paid the firm of Shriver and Williams for clothes to bury her. That same year, the county paid Beal Buckingham for the coffin and burial expenses for Elizabeth Parrish. She must have been a pauper, too, but that wasn’t mentioned in published records. Thomas B. Owings received $10.00 to provide a coffin, clothing, and the burial of Mary Ridgely.

David Fuss, a coffin maker, was paid for coffins for the son of Mary Mathews, and the daughters of Elias Warner, Thomas Bankerd, and Abraham Stultz. If you descend from Mathews, Warner, Bankerd, or Stultz, you probably won’t find gravestones in a local cemetery for those children because their families couldn’t afford that luxury. Perhaps someone scratched a fieldstone with the child’s initials and a date, but markers like that rarely survive very long. Some cemeteries did set aside a free area for pauper burials and your ancestor’s name might appear in their old records.

Try checking these offbeat Carroll County resources for ancestors who disappeared between the cracks if you suspect they fell on hard times.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County

Photo credit: Submitted photo

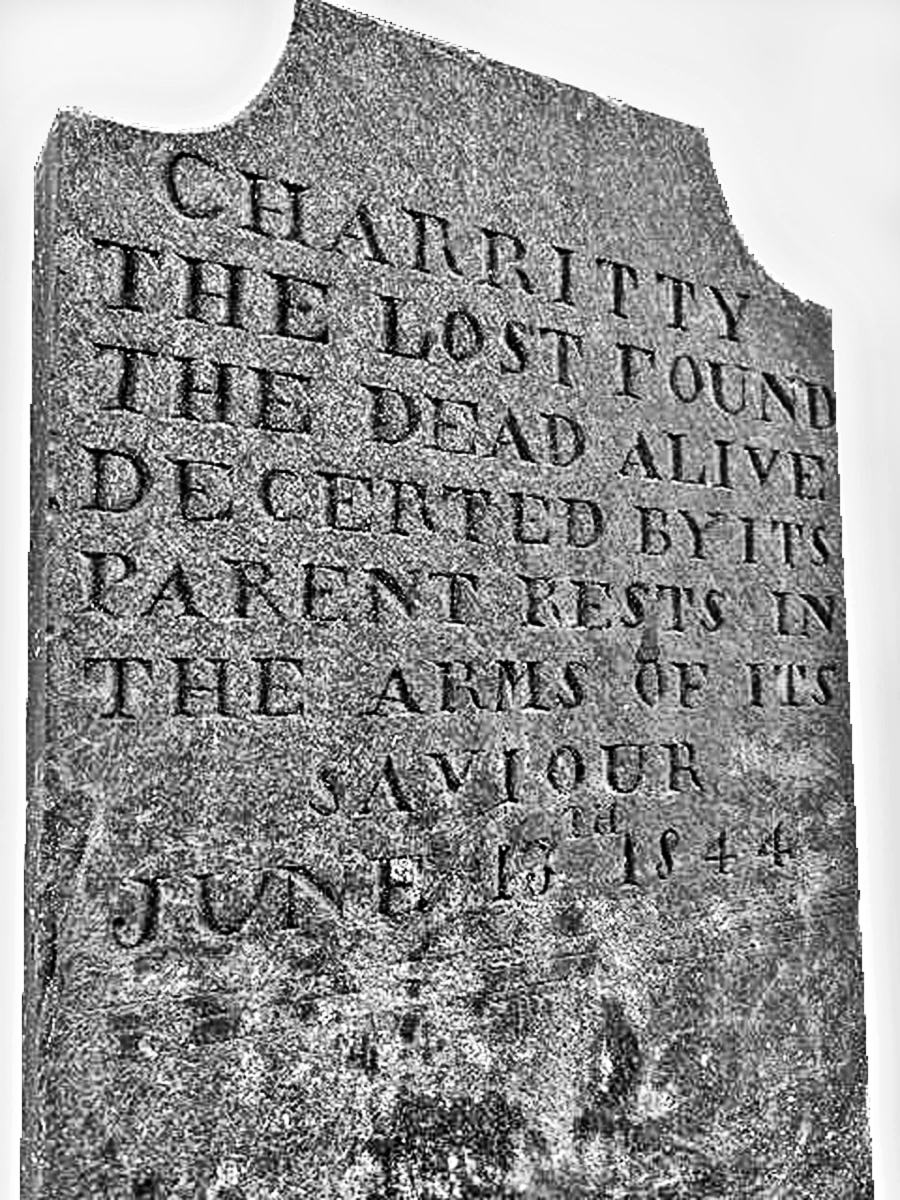

Photo caption: This gravestone, carved by Caleb McPeak, memorializes an unnamed child buried at Pipe Creek Church of the Brethren. It reads: “CHARRITTY: THE LOST FOUND, THE DEAD ALIVE, DECERTED [SIC] BY ITS PARENT, RESTS IN THE ARMS OF ITS SAVIOUR, JUNE 13th, 1844.”