Carroll Yesteryears

8 April 2018

Two Centuries later, Headstone Engraving Process has Changed, Need for Precision Hasn’t

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

At Mathias Monuments and Memorials, Dan Long, Jr. carries on a tradition of engraving tombstones that stretches back in Westminster almost two centuries. The techniques used by the first documented local carver have changed dramatically, but the importance of erecting memorials remains. John Beaver’s name appears on several large, handsome headstones made in the 1830s. One stands in Westminster Cemetery. It is unusual to see a carver’s name on an early stone as most men left no identification on their work. Another of Beaver’s stones, done for an uncle who

served in the Revolutionary War, stands in a family cemetery and bears a patriotic design plus a poem describing the uncle’s military service. John himself served in the War of 1812 and delighted in recounting stories of his experience before he died in 1877.

Andrew Beaver took over his father’s business in the mid-nineteenth century and passed it on to a third generation of Beavers about 1875. The final family member to produce gravestones was also named John. Following his death in 1906, Joseph L. Mathias purchased the business which has operated under that family’s name ever since although it is no longer family-owned. The business moved from Beaver’s original location along the old turnpike connecting

Westminster and Reisterstown to a site on the south side of Main Street in Westminster near Longwell Avenue and then further east on Main Street. Today various granite and marble memorials belonging to Mathias Monuments are located on a lot next to the company office at the corner of Main and Center streets.

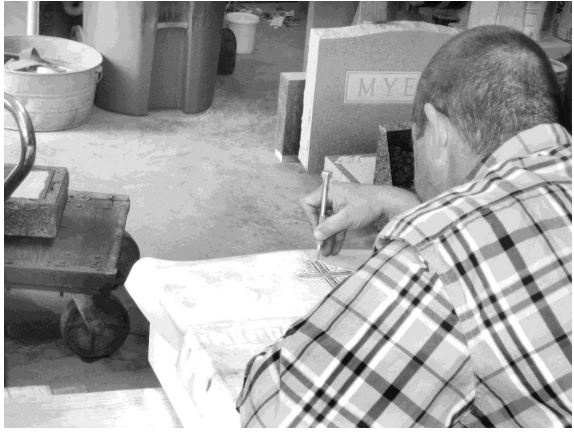

Dan Long took over engraving from his father about ten years ago and works in a shop behind the office. He rarely uses the metal chisels and wooden mallets that earlier carvers employed, but some of those tools can be seen at the shop. Looking at them it is easy to imagine what a laborintensive job stonecarving was. Today, companies predominantly in Vermont and Georgia sell monuments already cut, shaped, and polished to firms like Mathias where engravers like Dan add names, dates, and anything else a customer wants to personalize a stone. Unusual kinds of stone such as “black granite” or slate may be imported.

Sandblasting the inscription into the stone has replaced the tedious work of chisel and mallet. Today’s engraver glues a thin rubber sheet to the stone surface, then uses stencils to put the lettering and any additional designs on the rubber sheet. After the letters are carefully cut out to expose the rock beneath, the stone is set upright in a chamber where it is powerfully sprayed with a fine aluminum oxide grit. The grit bounces off the rubber surface but cuts into the exposed granite or marble as the blasting device moves slowly back and forth. Two centuries ago, a horse and wagon would have pulled the finished headstones to a cemetery and additional lettering would be chiseled by hand. Placing stones in a cemetery today is an entirely different matter and a portable sandblaster can be used for inscriptions, but the engraver’s job still requires patience and precision.

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Submitted photo

Photo caption: Dan Long, Jr., the engraver at Mathias Monuments and Memorials in

Westminster, puts the finishing touches on an intricate cross to decorate a headstone.