Carroll Yesteryears

13 May 2018

Woman Escaped Potato Famine, Sued B&O Railroad and Bought Eldersburg Farm

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

We are a nation of immigrants, survivors of myriad hardships. Today’s column features the story of a courageous Irishwoman named Hannah Dougherty who came to Baltimore to escape the Potato Famine of the 1840s and 1850s and ended her life in Carroll County. Several references in the Baltimore Sun of 1869 and 1870 tell of Hannah’s lawsuit against the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad for the death of her husband James in 1868. It took two trials

before Hannah, a widow about 38 years old, and her six children were awarded significant compensation. Who would have believed an Irish immigrant could have taken on the mighty B&O and won? There are some gaps in tracing Hannah’s story, but she appears in the 1860 census with husband James and three young sons living in Baltimore’s 14th Ward (an area known as Irishtown), near the B&O railroad yards. Hannah and James were born in Ireland, but the boys were born in Maryland, likely indicating the couple married once they arrived. The 1850s and 1860s saw large numbers of Irish landing in Baltimore, many of them soon employed by the B&O.

How James died remains a mystery, but the accident apparently happened “near Sykesville.” That was where Hannah and four of the six children lived according to the 1870 census. Two of the boys, ages 10 and 11, lived elsewhere, working for families near Libertytown in Frederick County while the 14-year-old boy and three younger girls were with Hannah. The lawsuit had not been settled in 1870, so it is easy to understand why farming out the two boys was an economic necessity. Sometime between 1870 and 1874 the B&O awarded the family roughly $4,000 to settle the

lawsuit. Hannah used her portion and those of her children to purchase approximately 185 acres in the Eldersburg area near present-day White Rock Road. The 1880 census listed her as a “farmer,” and sons Andrew and Edward, ages 23 and 21, worked on the farm. Three younger girls were “at home.”

The 1880 agricultural census for the Dougherty farm showed land worth $4,000. During the previous year the farm produced $950 worth of goods—probably from the sale of 450 pounds of butter and 600 dozen eggs, but who knows what else. The family owned five horses, two mules, 18 cows (including six “milch” cows), seven pigs, 50 chickens, plus a large orchard of apple and peach trees. By 1900 two of the Dougherty children, oldest son Andrew and youngest daughter Mary, were dead; two sons had moved away; and Hannah lived with twin daughters Sarah and Hannah C. who were 36 years old plus a young boy who was a “servant.” She disposed of her land in a series of transactions in 1898. When she died February 22/23, 1901, at age 70, she had $813.24 in the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank of Westminster and $210 in cash. Once her estate was settled, her executor divided almost $600 among her four living children and another person—not a small feat for an immigrant woman who could neither read or write!

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Photo credit: Submitted image

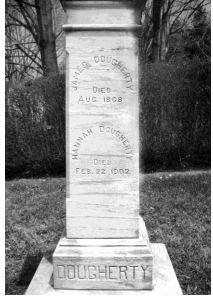

Photo caption: The monument to James and Hannah Dougherty in the cemetery of old St. Joseph Catholic Church in downtown Sykesville contains a few errors. James died in October 1868 and Hannah died in 1901, not 1902.

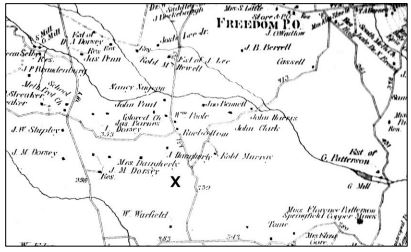

This detail from the 1877 Illustrated Atlas of Carroll County shows the location of Hannah

Dougherty’s farm.