Carroll Yesteryears

11 August 2019

Local Papers Reports on Post-Civil War South

By Mary Ann Ashcraft

Today’s newspapers, television, and internet share the plight of civil war victims around the globe and the struggles of agencies trying to help them. In the months following the American Civil War Carroll newspapers similarly reported the dire circumstances facing people in the warravaged South as the winter of 1865-66 loomed ahead. Westminster’s Democratic Advocate told of the “robbery and spoliation” in the countryside surrounding Richmond, Virginia, the former Confederate capital. “Nearly every farm within a radius of five miles of the city has been put under contribution by the marauders, and many of them stripped of every hog, cow and fowl.” Letters from Alabama and Georgia reported, “Times are very, very hard. Money is obsolete. We live almost without it.” Agents of the Freedmen’s

Bureau, a U.S. government agency formed to help newly freed blacks, suggested that “thirty thousand negroes will perish this winter in Georgia alone, and forty thousand more in Alabama.” A powerful poem appeared in the Advocate with one stanza that read: “When the cold northern wind blows chilly and rudely / And the rain patters hard at your windows and door / When you hear the blast howl, look around on your comforts, / and plan some good thing for the indigent poor.”

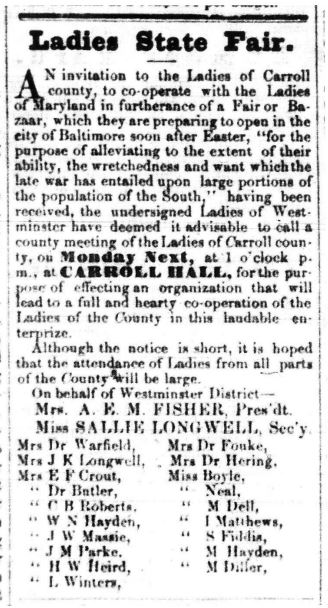

How would the people of Carroll County respond to these appeals? In spite of many deaths and serious injuries suffered by local men who fought for both the Union and Confederacy, Carroll fared better than the South – better even than Frederick or Washington counties to our west. To be sure farmers lost livestock; thousands of troops trampled the landscape; merchants’ store shelves were stripped, but homes and barns were not burned. Nothing happened to match what Union generals Sherman and Sheridan inflicted on Georgia and Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. On March 1, 1866, the Democratic Advocate carried the announcement that accompanies this article. Women from Carroll’s election districts were urged to join women from across the state of Maryland “for the purpose of alleviating to the extent of their ability, the wretchedness and want which the late war has entailed upon large portions of the population of the South.” Admittedly this help was coming after the “cold northern wind” blew across the southern landscape during the preceding winter, but help of any sort was needed.

There is something quite interesting about the Westminster names on this list. Some belong towell-known Southern sympathizers. Miss Boyle and Miss Neal each had two brothers in Confederate service. Mrs. J.K. Longwell was arrested, brought before the Union provost guard in Westminster, and asked to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. According to an account in Frederic Shriver Klein’s book Just South of Gettysburg, Mrs. Longwell indignantly responded to questions of her loyalty by saying, “I would give food to a hungry dog. I would even feed you, if you came to my house hungry.” The names of women from Carroll’s other nine election districts who participated in what became Maryland’s “Southern Relief Fair” are unknown, but by May 1866 they had raised $1,950.25 plus “a great amount of Provisions, and useful articles.”

Mary Ann Ashcraft is a library volunteer at the Historical Society of Carroll County.

Image source: Democratic Advocate

Image caption: This notice urging Carroll County women to participate in a state-wide effort to help the suffering population of the South appeared in the March 1, 1866, Democratic Advocate.